encounter

Mind over matter

Dhali Al Mamoon, Chittagong-based artist and teacher, and Wakilur Rahman, expatriate artist living in Germany, speak to Depart on issues that led them to conceive the exhibition Kagojer Chhayay or In the Shade of Paper. Following is an excerpt from the interview initiated by artist and writer RONNI AHMMED and MUSTAFA ZAMAN.

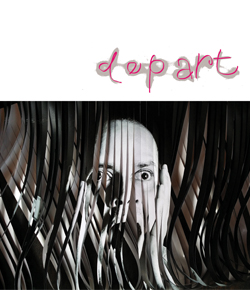

Mustafa Zaman: I would like to begin with a question for Dhali Al Mamoon. Your large installation piece where a series of hands moves mechanistically reminds one of the assembly line. Though in the write-up for the brochure you connect this to your childhood experience with toys, there seems to be an echo of the nightmarish reality the machine age. Does this piece address the issues of industrialization?

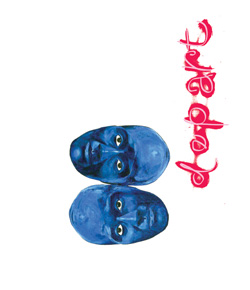

Dhali Al Mamoon: I am sure about one thing that there was no intention to create one definite meaning. Rather the work serves as a text with multi-dimensional purposes. It is connected to my childhood in the sense that as a child the movement of any toy gave me immense pleasure. And I also had the realization that it was I who instigated the movement. There used to be a feeling of ‘being in control’ and ‘being empowered’ due to the supremacy I had over the toys. As I was conceiving this series of moving sculptures, I wanted to inquire whether that very same connection of the humans with power and control as well as the media existed as it did between children and toys. Various references abound this work: there are materials, elements of ornamentations, depiction of people’s head being blindfolded by textual matters; there are also those features of the toys– paper alligator with folds, which prompted me to turn the mid-body of humans into many-folded breathing apparatus. If there was one particular aim, it had to do with the effacement of ‘gender identity’, so that all that were going on were not gazed upon from any gendered perspective. Aside from that, the multiplicity of meanings and purposes have been my actual intention.

Ronni Ahmmed: The concept of ‘Manufactured Truth’ drawn from Chomsky's 'Manufacturing Consent' seems to have been central to this exhibition. What is your (both artists) position vis-à-vis the question of ‘truth’? Especially, are you saying that one particular kind of truth needs to be produced and the other kind is redundant? Also, has the issue of doubt made you think– the question of whether there is any such thing as ‘truth’?

Dhali Al Mamoon: Wakil is the initiator of this exhibition. He is the one who first approached the daily Prothom Alo [the sponsoring organization] with the project. We had an understanding between us, and I conceived my contributions as an extension of what he proposed. By that time we began to study issues related to the media, even reflected on the idea of ‘manufactured truth’, ‘production of truth’.

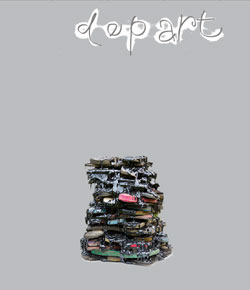

Actually we also want to ask: what is truth? I personally have drawn from the myth of Sisyphus to address such ambivalence with regards to truth. Information is certainly one of the primers for manufactured truth. It is through information that ‘truth’ of our age is being constructed. In the work which is based on the myth of Sisyphus the wall made of stacks of cut newspapers creates the sense of impenetrability of such continuous flow of information. I believe I have not been able to give it a completeness that it deserves.

Mustafa Zaman: Yet this is one of the most important pieces of this show, considering its visual and psychological impact on the viewers.

Dhali Al Mamoon: My aim was to display information stacked in the form of a wall. This is the very wall that people are unable to topple or climb– this simple idea of impenetrability is at the core of the work. The rest has to do with the aesthetic aspects and all.

Mustafa Zaman: Does this information-wall pollute human minds or society?

Dhali Al Mamoon: Since the US is the very centre of such productions, if we look at it closely we would see the entire ecosystem of ‘truth’ is akin to a maze– where people roam around without knowing who they are and where they are. That kind of reality is decidedly related to ‘power’ and its structure, and obviously it subjects people to a state of inertia in absence of interrogation and inquiry.

The fact that people are being continuously deceived in this kind of reality is what inspired me to plan this exhibition.

Mustafa Zaman: The title of the show – In the Shade of Paper– seems too poetic for an exhibition like this. Especially in the context of your work that strives to address the pathologies of our age regarding information and truth.

Dhali Al Mamoon: We did not want to have a definitive title as we thought it was better to have suggestive phrase for a name. As our main material was newspaper and the word ‘shadow’ has an all-encompassing feel to it, we thought this title covers both the poetic spirit of some of the works and the conceptual aspect of the whole show. We tried to avoid any heavy phraseology.

Mustafa Zaman: But it is a heavy arrangement for a conceptual exhibition, considering both the technological aspect and the overall display. All this creates a feeling of godya or prose.

Ronni Ahmed: The works retain a strong essence of realism.

Dhali Al Mamoon: There are two sides to this exhibition; and we two also represent two different essences of reality: my expression is very dramatized, while Wakil’s is very silent. Your observation is that the whole show has a prose-like tone, but I would like to stress the fact Wakil’s work is very, very poetic.

Ronni Ahmmed: But compared to his earlier works, this time around his work seems more inclined to the prosaic side.

Dhali Al Mamoon: The basic spirit that has been encapsulated in his work has a poetic dimension to it. For example the work that flows like a river across the gallery floor– where he displays childhood references such as paper-boats– is a very poetic work.

Wakilur Rahman: Everything is related to the character of the individual. We two have two different personalities and we also possess different taste. I believe in the domain of art we also have two different personalities. We are two temperamentally different artists wanting to communicate in two different ways. And our divergent temperaments led to divergent expressions.

I, personally, never want to move the viewer emotionally. What I aim for is the creation of a space that enables ‘thinking’.

Ronni Ahmmed: Do you prefer to be inspired by intellect alone?

Wakilur Rahman: What I strive for is a space that would initiate thinking. As for the drama, or emotion, I personally feel that my experience have guided me to where I am now. I feel that my proximity with the Japanese and Chinese artists play a role in my creative world. Look at Russia at the end of the ‘cold war’– all the statues and sculptures that had been built were torn down. These are creations that ended in futility, and that makes me sad. So I feel that there must be a way to communicate to people so that it would last much, much longer. I feel that it is only through thinking that this can be made possible.

Ronni Ahmmed: Are you referring to philosophy or just plain thinking?

Wakilur Rahman: An artist’s primary responsibility is to look at things in a definite way. We look at objects all the time, but we hardly ever think about them or contemplate on them. With every piece my prime objective always remains the same, which is to produce thoughts.

We pick up the paper on a daily basis and we attentively go through each and every news item; yet, in the end, it becomes an object of utter neglect as on the next day a new spread of news arrives.

In this exhibition, by way of exploiting the materials, I thought, my foremost ambition was to enter the discourses around power and truth– subjects that we are trying to touch on right now. The spectrum of issues that has to do with the news media– from the material to its character, which includes paper, production, news, a corporate system, and a decision making mechanism– everything has been explored, so that the whole process spurred the viewers into thinking. What I find most interesting about this show is that two different temperaments are encapsulated within a single space. Probably there are some aspects of our biographies that percolated down to our works. As I stay in Germany, the distance plays a role: Mamoon lives amidst the news and I observe them from afar.

I have been working with numbers and words for a long time, and from that tendency I could easily hop into a space that would solely be dedicated to the media and its making. That is how this exhibition came about.

Mustafa Zaman: You refer to a space– a thinking one. Do you conceive this space independent of time, place and the relations they have to the ‘subject’– the artist? You have displayed a tendency to refer to your childhood, which lends your work a poetic quality; Dhali Al Mamoon, on the other hand, is more entrenched in the realities of his immediate surroundings.

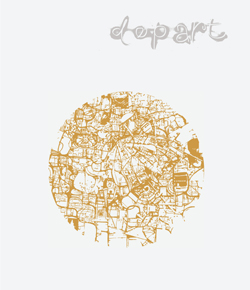

Wakilur Rahman: I would like to emphasize that as I address the subject matter of our choice I do so in a way that it enables me to depict how the media is controlling the world, as in the work The Globalization of the Newspaper, where papers were twirled into ropes to be used to give shape to a huge sphere symbolizing the globe.

We were careful so that the display did not rigidly follow the grid of the floor. Accordingly, we placed some works in a horizontal pattern and some vertical, or oblong.

Mustafa Zaman: Do you feel that meaning is a very important component of the aesthetic experience?

Wakilur Rahman: When I think up a conceptual work, meaning remains a significant part of it. But there are works that I do that reside beyond the world of meaning, as in the works that exploit the visual aspects by creating an atmosphere of sorts. The technical aspect and the space that come into existence becomes very important in those works.

Ronni Ahmmed: It is for this reason, I feel that in your work the surface and its texture predominate. You tried to explore all the possible combinations that one can achieve by exploiting newspapers Ð the material of your choice.

Wakilur Rahamn: I feel that it has emerged spontaneously. I have had the experience of working with this material before in Germany, and had the opportunity to realize that the scope of exploiting all its aspects is huge.

Ronni Ahmmed: I feel that it was an examination into how this material could be made to metamorphose– I am saying this in lieu of your earlier attempt at an exhibition.

Wakilur rahman: I am aware of the fact that the tone and the colour will not remain the same. Six months down the line, things will begin to look down. So, I would say that these works will forever be in a living process. If one wishes to collect them one will have to take to it for granted that the works will be subjected to continuous changes. Newspaper does not guarantee longevity.

Ronni Ahmmed: Newspaper or the media has a language that distorts truth. So, am I mistaken when I say that your venture exploits the power structure to critique its very existence?

Wakilur Rahman: Having spent years in Europe I have come to know one thing that the international art market and the components that go to build the whole spectrum, including collectors, galleries, and museums, have their own agenda. I have come to realize that the very profession I am into is very ‘near to the power’. I realize that it is a given. As an artist I can create the artistic product, but it is beyond my means to control its fate during an exhibition or sale. I don’t have any control over who buys it and where it ends up as a display.

Whenever there is an option for salability, there arises the possibility of a ‘society’. In Europe, the experiments that are being done in the arts have there place in the triennials and biennials. But these expositions are also sponsored by companies that have nothing to do with the alternative character of arts. The largest collections of highly experimental works of Garman art lie in the hands of someone whose father had come to his riches by manufacturing tanks for the Nazis. When I came up with the idea of this show, I thought it would be better if a newspaper sponsored it. And when I approached Prothom Alo, they were clever enough to except it without hesitation.

Mustafa Zaman: In the West, the 1960s saw a surge in creativity– what is often dubbed as ‘counter culture’, which was later usurped by the industry of popular arts only to turn artistic productions into hard currency. But, there must be some ideas that stand against power, or a spirit that always defies what is being manufactured by the people at the helm.

Dhali Al Mamoon: We must then zero in on the actual issue: there must be constant questioning. Interrogation is the only means to get over this situation; we must direct our questions first to ourselves and then to the art scene. Why art, what is the role of art and the artists? These are the queries that, I feel, need to resurface every now and then in our midst. This particular exhibition brings to the fore the issue of objecthood and beyond objecthood– the question of when art becomes a mere marketable object or product, a condition that ensures salability, and when art is art proper. I feel that when art goes beyond objecthood, it travels towards sensitivity, towards the territory of spirituality.

However, one thing must be taken into account that the market is always ready to see art as object by skirting round the sensibilities that I as an artist invested in it and the bodh (feeling and insight) with which I have brought it into being in the first place. Market always turns art into a marketable property as the socio-economic issues are also related to it. Market, economics, society, and how the society provides the framework for value judgment, and how and with what purposes all the other products are created and how the relationship of art with those are being determined– these are the issues that in the end decide whether an art piece is a mere object or a repository of sensibilities. So, time and place against the individual subject is of primary concern. Had the display that we have here been relocated to a European site the meaning of our art would have gone through a change. That is why, to me, thinking is art– it is the best entertainment humans can produce.

Wakilur Rahman: I know an art collector in Germany who only collects ideas. There is a British artist who, on a daily basis, travels by a bicycle to the local post-office and mails his photographic film to a collector without even finding out the results. And there is another performance artist who simply does things within a gallery space, of which no document has ever been produced; so no one knows what he does, but that he does is an issue of aesthetic significance. His recent project had been sold out beforehand.

Mustafa Zaman: If ideas too are marketable, do you feel that an ‘anarchic’ spirit of constant questioning and intellectual activism is of prime importance?

Dhali Al Mamoon: What I understand, in a very simple way, is that each artist has responsibilities. Evry artist is like a nurse who nurtures the sensibilities of the people. There are leakages that trouble our time, or impede the journey of the present generation, and there are various realties behind these predicaments. A true artist often reconstructs them, rebuilds them and, when necessary, eliminates them. She/he does her nurturing in many a form. The primary responsibility of any artists is nurturing of the cheton or spirit as well as the sensibilities.

Ronni Ahmmed: Media is the ultimate virtual space where news of a massacre, even on a scale of the one that took place in the BDR Headquarters, is being presented side-by-side with an advertisement. Therefore, how do you think you have been able to express this value-free state that exists in the media?

Dhali Al Mamoon: The world of the media in entirety is constructed with elements such as image and text; therefore it is nothing but a reflection of the reality. We understand the global scene through it, or may be able to imagine that reality from what is being proposed.

Ronni Ahmmed: The reality that is being presented is something akin to an illusion.

Mustafa Zaman: The very topography is chimerical. Represented reality Ð which is the world of the media Ð is making our sense of reality more turbid.

Dhali Al Maun: If I am to cite the example of the BDR massacre, I feel that we the people had no clue of what really was happening – neither when it began, nor even when it ended. What we came to know at the beginning and what we were privy of in the end were two different interpretations or truths.

Mustafa Zaman: What is real is lost forever, and we are stuck with what may seem like mere reflections of reflections.

Wakilur Rahman: The text we have written also cannot be considered as absolute. There are some reflections on what is beyond truth and reality. In the catalogue we talked about our childhood and also there are some thoughts on reality. But one of the main focuses of this show is how texts are in a constant state of flux. What we wanted to capture is the fact that what is perceived real has no integral whole. Texts always come in fragments. I myself have drawn on archival aesthetics to show this – series of words forming several windows is the theme of one of my works.

Ronni Ahmmed: Does this show tell the viewers to think in a certain sway, or read and interpret in certain manner as does the media?

Dhali Al Mamoon: I don’t think so. We worked from within an ‘objective condition’ – never trying to force the viewers into accepting a definite interpretation. I personally never believed in any fixed notion of meaning. I always try to address phenomena and also complex truth.

Mustafa Zaman: To avoid a fixed moral stance?

Dhali Al Mamoon: I personally feel that the bridge in this show, one that is exclusively based on Prthom Alo news and which is a work that uses up myriads copies of the supplement they ran on the issue, is a sign of incompleteness. Bridges indicate what is not operational in our society. When I personally had the chance to look at one such structure in Netrokona, I thought the concrete structure looked wonderful against the lush green– it looked more like a visually interesting monument. There are also bridges that use indigenous knowledge, when the representatives of the people fail to deliver on their promises and the people had make do with whatever they had to intervene. So, I have represented the unfinished government bridges to allude to our unknown destiny. And beyond the material and structural aspects, there is this archeological and even anthropological aspect to the bridge.

There are various aspects of this show by which the viewers may be stimulated and that may lead to a proponcho or discourse.

Mustafa Zaman: Between physical reality and consciousness, which aspect do you think was more important to you as far as this exhibition is concerned?

Dhali Al Mamoon: I feel that both are equally important. Visual art is close to music. If it becomes too intellectually rooted then the visual aspect is undermined. I strongly feel that the motive behind the work should not come to the surface as art always communicates at the levels of instinct. Viewers take it in instinctively.

Wakil’s work is more on the abstract side, mine is more physical; together we represent both end of the spectrum– absence and presence.

Mustafa Zaman: One last question, why do call this exhibition art exhibition, why did not “installation art” exhibition?

Dhali Al Mamoon: It is after all visual art, any installation too is visual art. We tried to avoid the word “installation” as we chose not to bracket the works within a single conceptual frame.

Wakilur Rahman: Installation is what is usually dubbed as site-specific art. Here we have amassed various kinds of works that are proposed as objects. So we thought the word installation would not be expressive of that spirit.

The exhibition 'Kagojer Chhayay' took place at Bangladesh National Museum, Dhaka, from March 20 to 30, 2009.