Features

Art, ritual and the continuation of rural lore

According to most scholars, the earliest evidence of painting from this deltaic region dates back to not more than three thousand years. In the absence of any specimen from the previous ages, one may find its residue in the form of art that connects the present day practices to those of the past, (especially through “broto alpana”), one which continues to this day in one form or other.

Elements that seemed to give off a sense of “the primordial” are still surviving in folk art, in which we may find a continuation of the art of even the pre-historic age. The commitment to repetition and continuity is what rituals are all about, and through this regenerative principle, a visual culture based on certain belief-bound scenography is kept alive and handed down from generation to generation. Dwelling on the physical elements that are in use in all forms of rural art practices, we come to realize the ephemeral life-span of such productions. Done on clay-potteries, they are discarded as soon as they have served their purpose following the ceremonies they were an important part of. What is valued in the end is the lore, which is an eternal source of inspiration for every generation.

All forms of folk art are deeply linked with communal life as well as rituals and beliefs. The rural artisans came under threat of extinction only when traditional life was thwarted in the face of colonial incursions. The surge of interest as well as the effort in archiving these time-tested art forms among some of the urban elites in the nineteenth century can easily be linked with this “new order”, one that began to dislodge the old socio-economic matrix. As the anti-colonial, nationalist movement gained momentum, these groups of people became more intent on saving/preserving what they began to consider as national heritage. Though they actually formed the upper crust of the urban educated gentry, their interest and work sent them meandering through the rural landscapes in search of art objects in the subaltern households.

Their attempts were later to materialise into successful exhibitions and also archives to house the acquisitions, as has been recorded in the initial heaves in 1931 and 1932.

The texts that flowed from such early efforts, adequately testify that the fervour for folklore was fueled by the compulsion to inculcate in urban masses a strong sense of tradition and had very little to do with the rural ground reality.

It can be safely deduced that the process of initiation of the urbanites into the realm of the rural traditional art forms were started by the very same people who were gradually turning into sahibs due to the Western influences they allowed themselves to be exposed to and the education that crystallized them.

Following partition, in 1947, Shilpacharya Zainul Abedin, organized two folk art exhibitions of his own accord -- one in 1954 and another in 1958 -- in the art institution that he helped to bring into existence. As a follow up to those efforts, he started to build an archive of folk art in his newly-established institution. But the enterprise got nipped in the bud due to non-cooperation from those very students whom he had earlier sent to Europe and America to obtain higher degrees in modern Western education and later instated as teachers of his institution.

The rift that polarized modernism and tradition not only manifested in such antagonistic stance of two successive generations, but also in Zainul’s divergent styles.

However, in the 1970s, Zainul took an unusual initiative with some decisive outcome in mind. At that point of time, he concentrated his efforts on establishing a folk art archive as well as a village for the artists in Sonargoan2 Zainul’s action testifies to his realization that the attempts at archiving rural art would be futile if the tradition faded away.

But still he could not envisage the fate of folk art, a form that is an expression of a lifestyle– or to be more specific– a reflection of a certain socio-economic reality, one which could not be kept alive through patronage alone, as is possible with all forms of modern-day art practices.

In 1960, artist Quamrul Hassan, Zainul’s associate and one of the co-founders of the art institute in Dhaka, (who once was an avid follower of Gurusaday Dutt, the principal force behind the Bratochari movement) also set up an organization by the name of Design Centre. Kamrul left his teaching job to begin his intervention through design and art practices that strove to lend salience to folk art.

The folk art fairs organised by the Design Centre during the 1970s throughout 1980s, were critical in generating interest in rural art forms among the urban educated mass. Quamrul also had some specific plan aimed at patronization of the rural artists.

Also of significance were the activities that government organizations planned and implemented. The Bangla Academy played its part by arranging folk festivals and programmes that would have an impact on the city dwellers playing a catalytic role in initiating a shift in interest.

Though, in retrospect, it is difficult to be conclusive about the outcome of these programmes and festivals that have been perceived as a way for the urbanites to reclaim the rural lore, since they have become a regular phenomena following the early 1970s, the fact remains that the myth that folk art is disappearing fast was disseminated through these interventions. This is the message that the organizers of such festivals have regularly been sending across. The package of folk festivals and programmes has always been delivered with this warning; it was an integral part of the rhetoric surrounding the efforts in revivalism.

My contention is that the process of the disappearance of cultural practices is very slow, and sometimes even natural. And only in certain areas and specific cases intervention is justified and may even be needed to keep thinks on track.

Intervention sometimes leads to disastrous consequences. The army of concerned social workers who emerged from the elite class to revive kantha art has only been able to lead astray the traditional project and turn it into a vehicle for their own financial gain. The diversification that followed also became a major reason for the disappearance of kathaÕs basic character.

Institutionalized religion also shares the blame for the extinction of some of the art forms that once were an integral part of the rural culture. One such important form was pat painting. That the pat painters were neglected by both Hindu and Muslim communities, enforced a gradual change of profession on the part of its exponents. The departure from the myth-bound exuberance of the pat to the other socially acceptable and viable occupations was slow, but it translated into the inevitable– the disappearance of pat paintings from the rural cultural landscape of Bangladesh for good.

Experts’ opinion on the subject is divergent. According to some the communities of “professional painters” among the Hindus once were an integral part of the social structure, occupying a place in the hierarchy as caste Hindus who lived with honour. It has been encapsulated in the Brahmabaibarto Purana, which says that ‘after attempting to draw pat paintings that are antithetical to tradition, the artists were cursed by enraged Brahmans, hence their status as outcasts.’

The element of what had been “adversative” is yet to be identified. However, historical evidences suggest that the heritage of pat painting in this land could only be linked to the Acharya shamprodai or community that has said to have been involved in producing Gazi pat for the Muslims. Some believe that like the Buddhists, the Muslims too resorted to arts to spread their faith by glorifying their saints and heroes in pats that are as always story-telling. The Muslim intervention may have coincided with the writing of the Brahmabaibarto Purana (13th Century).

Gurusaday Dutt had also happened upon a story of the pat artists who were made outcasts in the face of social injunction. The story goes like this: ‘During the ancient time, someone among the pat painters simply set out to paint a pat without the approval of the Lord Mahadev (Shiv). Thereupon when suddenly Mahadev appeared in the scene, the pat artist hid the brush in his mouth, thus making it unholy. As a result Mahadev cursed him and he became an untouchable and a source of scorn in the eyes of the society.’ Outwardly, this story may seem imaginary and meaningless, but perhaps there may be some hidden historical truths inscribed in it.

Framed in an allegoric mode, the story alludes to secret practices. The expression ‘keeping the brush in the mouth and making it unholy’ prompts us to surmise that secretly the artists were engaged in producing art works that were not socially approved. They might have been forced into such (mal)practices to avoid starvation, but by doing so they fell out of favour forever.

There are evidences that the Acharyas of Mymensingh and Faridpur regions were once engaged in various visual practices– they painted all kinds of pictures. Making idols of temple mandaps (platforms) was their foremost responsibility, but they would also work as painters. Some experts are of the opinion that the fall of the Acharyas from the social hierarchy made way for the kumbhakars (potters) to take up the job of painting to fill out the vacuum.

This is not an unlikely scenario. There are special kinds of Lakhsmi shora in existence, which are made by the Kumbakars, but are known as Acharya shara, and are the costliest.

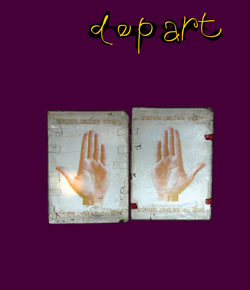

Perhaps this Acharya shora is the only evidence of the shastro-based art practices on shoras that has survived the test of time. It still continues to marvel us as a living form of a slowly fading culture.

After surveying the present day art practices on the rural front, one may conclude that it is also true that the religious belief that continues to exert influence on the people of this region also ensured sustenance of some of the major art forms. The most illustrious examples are– Lakshmi shora and Manosha ghat (small water vessel) made by the Kumbhakars, and Karadi chitra of the Malakars.

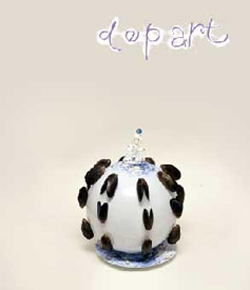

Other than the above-mentioned traditional art forms, there is only shokher handi from Rajshahi which is linked with religious rituals. The traditions of secular folk art in the rural cultural landscape of Bangladesh have almost died out. Yet, the opportunity is still remaining for us to look at the existing arts forms from a vantage point of our era that had seen some new crossroads in both knowledge and culture studies.

Efforts must be taken to discover the true value of these art forms and also to examine them under an analytical light they have always been denied. The research institutions need to take the initial step by involving enthusiastic youths for field works. To be able to map the existing art practices is of primary importance if we are to dispel the urban misconception surrounding all traditional art forms. Once the ground reality is revealed in its actual constitution, the semiosis of this very art form would slowly become a chartable pathway. This, in turn, will not only benefit the country, but also make way for the creation of a decisive body of knowledge for whole humanity to fall back upon.

Translation : Depart Desk

Notes

- Brato alpanas are artistic flourishes on potteries that serve as iconic pieces in religious rituals.

- Sonargaon was the reputed capital of Isha Khan, one of the valiant regional kings who successfully resisted attempts by the Mughal emperor Akbar to take over Bengal, according to most Bangalee historians.

Nisar Hossain is an artist and researcher, and teaches at the Faculty of Fine Arts, University of Dhaka.

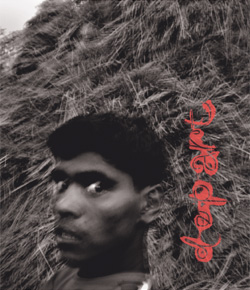

Photos : Nisar Hossain