Singled Out

Post-funeral of anti-form : Dispatches from Vienna Art Fair

The 7th edition of Vienna Art fair, in the first inspection, exudes the air of a genteel trade jamboree. But, I meet Pawel Althamer – the world renowned polish sculptor, pedagogue and instigator, in the 'Zone 1' display area, which is sponsored by the Austrian Ministry of Education, Art and Culture to give galleries the possibility to exhibiting individual artists in solo booth set-ups – which is particularly devoted to installations and extended presentation beyond the pressure to sell. Althamer appears as an old, naked man with striking resemblance to John the Baptist and he is discovered alongside a coterie of polish art students creating a massive installation with waste products, but with the naked man as the center piece.

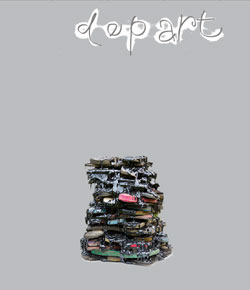

Karla, one of the students, fervidly counters my label, of their ongoing project, as an updated constellation of 'social Sculptures' a la Joseph Beuys' prescription, and stresses how in an inter generational dialogue the artist(s) transforms (art)historical material both intuitively and rationally as a current question posed in the language of contemporary art and calls the naked old man their model and references Walter Benjamin to state their case of using waste objects to create art in a postconceptually arid theoryscape.

In his first appraisal of surrealism, 'Dream Kitsch', Benjamin mobilized the analytics with reference to the accumulation of objects in his parents overstuffed apartment in Berlin that, surrealists correctly don't perform the dream-dissection and anal-analysis of the souls but of the objects.

The most analyzable feature of contesting layers of contemporary time, Benjamin contends, is mass produced, commonplace object, and object is:

'…the last mark of banal, with which we clothe ourselves in dreams and in conversations, in order to take up into ourselves the power of the extinct object-world.'

But, isn't the object-world dead because its forms are fixed and frozen, although the object-world is coded, freighted and invested with desire, power and sometimes rapidly and exceedingly mutating social meaning -- I wonder.

In 'Dream kitsch' Benjamin notes that what formerly worked as art, always began away from the body, through mass-produced objects, the object-world shifts towards the individual subject, peeling away emotions, foregrounding fantasies, acting like mass produced image or the montaged fragments, in that it meets the viewer halfway. Hence, mass produced objects, kitsch and clutter demand their right to exist and to be decoded; for they have overridden our traditional relationship with objects, including art-objects.

For the consumer, mass produced object:

'…offers itself to his groping touch and finally builds its figures inside him to form a being, who could be called der moblierte Mensch (an ornamented person or a tenant).'

Objects inhabit us as we inhabit it, the object-world, the frozen world of thing-forms beset us in a series of networks: the complex web of relationships, desires, past experiences, affections, and so on, which colors our raw perceptions and its understanding and constructs our reality. Our reality is a purely relational grid: one can only think of reality as, again, as a network, a net over the entirety of objects, over the totality of the real. The consensual reality inscribes on the plane of the real; and this other plane which we call, 'here' – the plane of the symbolic.

Structuralist linguistic theory – schematized by Ferdinand De Saussure – has regularly been deployed in order to assert that elements in the consensual reality may be broken down and interpreted through its conceptual framework whereby the link between signifier and signified is arbitrary and controlled by politics; e g the relationship between real fighter plane – the object, and the word fighter plane and the words meaning to a receiver is absolutely arbitrary and this relationship is controlled by hegemonic politic of the Kapital.

Objects are not words and they can't be made into words; they stand forever, and mysteriously, beyond them. In seeking to explain the relationship between objects and words, we are constantly brought up against the limitations of our knowledge of our reality.

Reader, are you, like me, having a sense of déjà vu? Is it still 1969?

2

The term 'concept art' was arguably first used by Henry Flint, a writer and musician loosely associated with the Fluxus movement. In 1961 he postulated a kind of art which consists of 'concept"'; In 1968, Sol LeWitt famously stated, 'the idea is the machine that makes the art.' The conceptual artist mimics an absurd producer who, in the heydays of the late 1960's and the early -70's interrogated the new Kapitalist relationships, the fetish of information, communication technology and the desubjectification of production. Of course, the ground breaking exhibitions like 'Op Losse Schroeven' and 'When Attitudes Become Forms', which led to widespread protest, cancellation of a planned Joseph Beuys exhibition and Harald Szeemann's resignation from the directorship of the Kunsthalle – not only culminated in movements capturing the larger contours of the art – Arte Povera, Anti-Form, Conceptual and Land Art – of the moment, but, they inaugurated an innovative approach of de-emphasizing the material presentation and making the publication the site of the exhibition, challenging all existing and future categories and introducing new curatorial strategies.

While most of the comparatively interesting works of the Vienna Art Fair are, theoretically, derivative and feebly attempts to capitalize on conceptual arts' formative and form-giving tenets, they immensely profit form cultural specificities that required the curators/galleries to coalesce their inquiries around and venture into particular terrain: the psychogeography of a post-concept and (post-)state European Union.

A pattern of hegemonic imperialist cultural reality, and a historical experience of resistance against empire, inform the works of the artists' commune, State of Sabotage (SOS) in ways that make it an attempt to subvert the causal fetters of consensual reality, by rewriting a proactive and insurgent map of the idea of Statehood.

SOS' Alfred Goubran states: The State is a system of rules, a regulator – machinery that administers our social needs and which is maintained by us. The legal subject expands itself as an individual for the state. It expends itself as a living being for something that is not a living being. It expends its vitality and its children for something that has

No biological existence. That is why state cannot grow, it can only be developed. What the individual gets back from state is always less than what s/he gives to it. And above all s/he never gets back any life time. A small amount of what is taken away from the individual – tax, fees etc – benefits other individual and the bulk serves to preserve the state. Preservation of state is characterized primarily by one thing: state's emergence. Hardly any sector today is unaffected by the emergence of the state. They are the state and pay tribute to their tribute in the form of dues – either in cash, or by relinquishing sovereignty and competencies. Especially in those sectors where the state seems to be intervening, the direct benefit is that the state legitimizes through its assistance.

SOS' believes, in order to exist state consumes the individual who made it but, SOS is an art state. Art itself represents the foundational myth of SOS and continues to invent new myths in the blueprint of others that would allow the art state to claim anything like an identity and or essence and thereby dispose of internal mechanism of antagonism. SOS aspires to be a Riemannian space of higher dimension, constellation of unconnected spaces that can be tacitly connected and attached to one another in an infinite number of ways, not unlike, jazz music.

State art in at the art state does not fantasize locations outside of state power. Instead it acts from the empty center and continuously occupies and displaces the blank spaces anew. Robert Jelinek, one of the mouthpieces of SOS, tells me, in tandem with the internet and the unlimited exchange of goods, the SOS movement, like many other micro-nations, has reinvented itself in the last five years and generates at least 500 real locations/entities where 'citizens' assemble to cast themselves as new kings into the gears of the global production machine – who perpetrate the redefinition of stipulated border demarcation, which have UN recognition, where underground cults form their own economic, monetary and belief systems. SOS, according to a gallery statement, has been persistently growing into tangible location and a miniature social laboratory; since august 2003, SOS has issued flags, postal stamp, coins, at least 1000 internationally standardized passport to 'illegal aliens'. The Italian SOS consul travelling by car thorough Europe, obtaining entry stamps in his SOS passport, achieves de-facto recognition of SOS in several countries, including Slovenia, Switzerland, Monaco, Andorra, Yugoslavia, San Marino, Seborga and Italy.

3

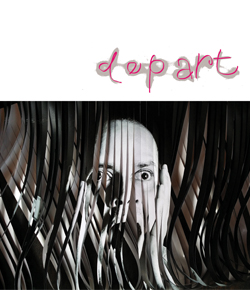

SOS and Pawel Althamer, interestingly provide an underlying premise and the background for the amazingly powerful works of Nil Yalter – curated by Derya Yucel, as part of a city-wide exhibition, East by South West where Vienna's leading art galleries take part and invite internationally renowned curators to organize a show to launch, in Žižek's parlance – in a short circuiting way – effective critical procedures to the cross wires that don't usually touch the contesting strata of realities-stories, fragments, slivers – to interrogate dominant power relations through the critical lens of an artist who is constantly and ineluctably marginalized and disavowed.

Barthes notes, meaning comes not from the objects photographed; the photographed objects induces associations of ideas and inaugurate a processes of signification, controlled by politics, stable to a degree which allows them to be readily constituted into a readymade semiology. The power relations and the meaning it generate are a transcendental horizon which makes our reality meaningful and when we are deprived of this transcendental network, that is, of the fantastic coordinates of meaning, we are no longer engaged participants in the world; we find ourselves confronted with things in their nominal dimension: for a moment we see them the way they are, in themselves, independent of us – or, as Proust put it in a wonderful formula, as a spectator, so to speak, of one's own absence.