contoured

Social activist artist Shuvaprasanna

Art for art's sake is a philosophy of the well-fed.

— Frank Lloyd Wright

Though most artists create, compelled by an inner urge and each creation is unique, it is also essentially a reflection of the dynamics of life in a given time, space and society. During times of struggle due to oppressive regimes or natural disasters, be it in the East or the West, artists are seen using their creativity to voice individual and collective anguish in search of some light at the end of the tunnel. In the grandiose Russian art of Stalin's era or the poster art of Hitler's Fascist Germany, artists have continued to create art and also perform in a dualist mode, as overt publicists and underground subversives. While Henry Moore's charcoal drawings recollect the horrors of world war as experienced by Londoners huddled together in bunkers, the work during the pre-independence era by our own artists such as Ram Kinkar Baij, Somnath Hore and KG Subramanyan amongst others is seen to echo a nationalist fervour in search of a rooted identity.

The role played by the Bengal School, the Tagore family and Santiniketan as an artistic centre for socio-political reforms, is well documented. Works such as Abanindranath Tagore's Bharat Mata and Nandalal Bose's painting for the Haripura Congress made at the invitation of Mahatma Gandhi, are luminous examples of this genre that assimilated international influences within oriental philosophy. More recent examples of Indian art resonating with the prevalent economic deprivation and socio-political scenario include work by Bhupen Khakhar, Neelima Sheikh, Atul Bhalla, Chintan Upadhyay and G R Iranna and their contemporaries. Raising issues around freedom of thought, gender inequality, environment and human rights in a newer context, they reaffirm the significance of 'art for society', beyond the thrust of 'art for art's sake'.

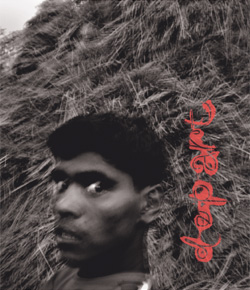

Bhadralok Sri Shuvaprasanna Bhattacharya affectionately known as Shuvada by his juniors and Shuva by his contemporaries is an accomplished artist whose multi-layered oeuvre is immersed in a passionate concern for society. The aesthetic genre of the skilled portraitist and painter even as a young boy has been inextricably intertwined with the city, its people and their struggles. The city of joy, his abode and playing fields since birth, its crowded localities bustling with life in cheek by jowl dingy tenements within the cluttered lanes and by-lanes, 'garbage-like with the poor and the destitute sack-of-bones men and women and their rickety children', make recurring appearances in his imagery, juxtaposed against the sparsely inhabited palatial mansions, offering a stark contrast. Then there are street processions, public meetings and performances around ideological battles that he has witnessed or been a part of, which get soaked in his renderings around socio-political and material realities of the urban city's public life.

Shuva took to art as a profession and joined the Indian College of Art and Draftsmanship at Rabindra Bharati University despite stiff family resistance and at a time when the prospects of any work, money or recognition looked bleak for an artist. The determined young man with his fortitude and talent in drawing and illustration managed to sustain himself and carry through his art college studies with meagrely-paid odd assignments for portraiture during festivals and fairs and design work for newspapers. Rising phoenix-like from all such tribulations he continued to struggle and generate a remarkably varied artistic outpouring over the last four decades encompassing realism, surrealism, abstraction, figuration, still life and beyond.

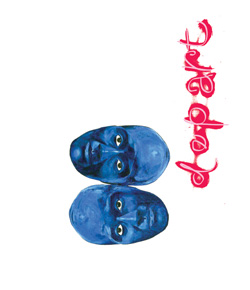

Though the artist started working as a professional artist in the 1970s, the ethos of his art and its ideology stems from the tempestuous era of the 60s in Calcutta, deeply rooted in the realities of the time. The surrealistic tone and treatment of his images in series such as Lament, Metropolis, Illusion and Wrapped seem to reflect the unease of a struggling artist trying to make a living in the tough city. The struggles of people in poverty stricken and strife frayed Bengal, alongside its intellectual rigour, survival instinct and socio-political consciousness run as undercurrents in most of his work of the early decades. His painting 'Calcutta 71' from Metropolis encapsulated the horrors of Bangladesh strife and the resulting agony so evocatively that Mrinal Sen decided to use it as the central image for his film on the subject.

The social activist artist, who lived for many years in a house close to the College Street, has been a witness to many social and political battles fought by students under various ideological banners. He joined some of them, attended public meetings, watched speakers on dais, participated in street processions, partook of cultural functions and observed people amidst crowds, subsequently figuring them in his work. Given his talent as a portraitist, he was able to gain an easy access to some great leaders of the time and his repertoire includes portraits of former President Sri Rajendra Prasad, Governor Srimati Padmaja Naidu, Chief Minister B.C. Roy and visiting dignitaries Soviet President Marshal Voroshilov and US ambassador John Kenneth Galbraith. There are other canvases with narratives of specific incidents, occasionally in satire coated with pathos, such as the painting of rag-picking children watching from a distance their Marxist Chief Minister Jyoti Basu inaugurate the Calcutta tram sitting on a horse-driven British period carriage specially brought in for the occasion! The city's forgotten emblems- the statue of Bengal's pride, Noble Laureate Rabindranath Tagore, turns into a resting place for crows in one painting while rats are seen to have a ball playing around industrialist Hariram Goenka's statue at Curzon Park in another.

The city's underbelly, its urban realities, the all-pervasive paradox of violence and Naxalite movement alongside its vitality and sordidness appear in Metropolis Re-visited, echoing more than disquiet for social inequalities. The nightmare of people suffering from draught and famine are brought into focus in Man & Space series. Then there are Calcutta Black and White and Metropolis: Portraits of Calcutta, part of the Calcutta Tercentenary year drawings and paintings, predominantly in B&W, sepia or burnt amber in charcoal and acrylic depicting the city's urban milieu, its squalor and gloom, decadence and struggles, alongside its intellectual rigor and the cultural ethos of the 'Mahanagar'. The expressions of dismay are often overlaid with a sense of hope that reflects people's survival instinct in an interesting fusion of symbols and images in series such as Touch, Dream, Abode, Birds, Middletone, Illusion, Night-Watch and most recently Expressions. There is a recurrent appearance of the omnipresent crow perched on parapets and wires on empty rooftops in drawings, paintings and prints. On his fascination for the ominous creatures–winged birds, crows, owls, cranes, eagles and storks with an occasional appearance of a feline, dog, donkey or another specimen familiar to the city– he says, 'I like them because they cannot lie. They don't pretend'.

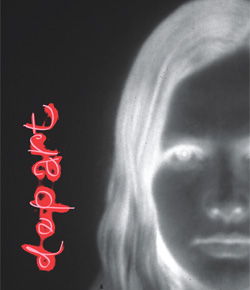

Human predicaments and anxieties are etched in a subtle juxtaposition of selective forms and contrasting colours in all his work, be it the wounded man, street boys or stray dogs in search of some food. The artist takes his engagement with these themes to another level in the Wrapped series with its dramatic and somewhat sombre appearance. In a philosophical mode, the work explores the futility of amassing wealth when life is so unpredictable, while it also reflects human susceptibility to hide or wrap up feelings or sins.

The surrealistic streak reflected in much of the disquieting aspects of the artist's work up to the late 90s takes on a different appearance at the beginning of the new millennium as his creativity matures further to meander through metaphysical themes. The myth and magic of Durga, Kali, Ganesha, Lakshmi, Radha, Krishna and other legends is rendered in diverse presentations which retain the earlier societal links. The sensuous lyrical narrative of Radha and Krishna appears without the ornamentation generally associated with the icons. The centrally placed hollow cylindrical figure, its puppet-like head loosely linked to the rest of the body in varied 'mudras' or postures, 'is inspired by classical and folk cultures of India including large asht dhatu Chola Krishna and small Bishnupura Krishna figurines in terracotta as well as Rabindranath Tagore's Gitanjalee amongst other sources', says the artist, replaying the significance of festivity in social and community life in rural Bengal.

Besides his artwork in drawings, graphics and paintings, the social activist artist, a man of many parts, has also worked in sculptures and installations. His creative thrust for socially relevant themes, extends to art forms such as poetry, illustration, teaching, designs for book covers, logos, posters, costumes and theatre sets, besides writing articles and weekly columns for papers and periodicals and a book on contemporary poetry and illustrations which he edited jointly with Shakti Chattopadhyay entitled Anarchy and the Blue that received critical acclaim. A people's person, Shuvaprasanna strives to reach out and share, dismantling the notion of a reclusive artist or the exclusivity of fine art as 'high art'. Coming into contact with the marginalised as well as political and eminent personalities quite early in life, the socially committed artist has always nurtured this urge to do something tangible for the community. The on-the-spot painting event for children that he organized when just 17 to encourage young talent and instill a sensibility for the environment in the community—the green brigade (Sabuj Bahini) art fair– was probably his first step in that direction. The open air cultural fair at Calcutta Maidan that he later organized was so successful that it turned into a weekly affair followed by the Market Square event and other community projects that he took up in the late 60s.

Shuva also played a significant role in the development of Bengal's graphic movement as part of a collective journey with his contemporaries. In keeping with the socialist spirit and idealism of the times, and the demands of the printmaking process and its constructs, Shuva shared the studio space and facilities as a member of the Society of Contemporary Artists with Lalu Prasad Shaw, Shyamal Dutta Ray, Suhas Roy and others, working in shifts by rotation. Given the medium's ability to multiply, communicate and enrich the environment at a more reasonable cost, the group organised exhibitions at fairs and during festivals, selling prints for very little to popularize the form amongst the educated middle class householders and intellectuals. But their attempts were thwarted by market forces that dominated the already constrained art scene. Undeterred, Shuva continued to refine his own technique, using the finest inks and the wood from jackfruit tree for which the wood engravers of Bengal have been known for since centuries.

Though there were hardly any takers for prints in India at the time, Shuva managed to sell them well during the various European sojourns that kept him going. The German interest in his work and the associations he formed there left a significant impact on his aesthetics and socio-politico-cultural philosophy, leading to some fruitful artistic exchanges. It was during one such European exchange visit that he also went to Paris where he came across the Ecole Nationale Superieure des Beaux Arts. The liberal training system that he saw there inspired him enough to set up a similar teaching institute in Calcutta- the College of Visual Arts, in 1975. He ran the lively art school until the age of 90, a vibrant community where many young artists of today got their initial training including young Shipra whom he married in 1980.

The institution maker also founded ArtsAcre, which he says 'grew out of a necessity as many of my students after graduation from the College of Visual Arts wanted to work in a spirit of solidarity and under my guidance'. The artists' commune and studio spaces that he came across at Dortmund where artists could work with creative freedom and also display and sell their work was the inspiration behind ArtsAcre. Its foundation stone was laid in 1984 by Pandit Ravishankar and three years later it got inaugurated by Shuva's friend and mentor German author Günter Grass with a first ever exhibition of his graphics in the gallery. Shuvaprasanna has now re-constituted the art centre as a Trust in a more ambitious embodiment at a new space located at Rajarhat, re-naming it ArtsAcre Foundation. Designed as a financially self-sufficient and professionally managed multi-fold cultural institute, it aims to promote visual arts, film, and performance arts.

A fatherly figure in the contemporary Indian art circuit, the idealist-socialist is hard working and determined, full of ideas and energy, ever ready to help others. 'I am not an island. I am a part and parcel of society. So each and every work of mine is about our time, our people and our society, though it is not like news reporting but my creative reflection,' says the artist as he takes the vibrant city's tradition of conscious intellectuals forward. 'I am not a politician but ready to join in rallies rather than be a silent witness to oppression', he declares.

Given his unstinting commitment to a life in and for art and his indefatigable engagement with social issues, the artist has in recent times extended himself to public protests in support of agitating poor peasants and against the state's anti-people policies and suppression of spontaneous popular movement of the rural masses in Bengal, some would argue at the risk of art taking on political colours. But for Shuva human right issues have an emotive appeal that get mirrored in his life and art, deeply etched and subtly highlighted, as a universal challenge of existence. In constant touch with the society, the indefatigable talented master artist is a pioneer. He continues to patronise several cultural organisations as advisory board member and contributes his talent, time, labour and resources to support various creative initiatives. Focusing on the experiential impact of the art, which involves a closer engagement of the heart and mind to resolve difficult social issues, Shuva's art repertoire is his effort to communicate, inform, educate, question, build bonds, enhance self- esteem and celebrate life. To quote Aristotle, 'The aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance.' So believes, apparently, social activist artist Shuvaprasanna.

SUSHMA BAHL, MBE, the author of 5000 Years of Indian Art and editor-contributor of Black Brown & The Blue- Shuvaprasanna (2011- Roli Books), amongst others, is an independent arts consultant, writer and curator of cultural projects, based in Delhi.