Features

Foregrounding unsituatedness

photogenic vs auteur architecture in Dhaka

Built as a modern day wonder, the iconic/phallic gesture that is the parliament building in Dhaka sits at the middle of its sprawling site at Sher-e-Bangla Nagar as the ultimate embodiment of autonomist aesthetic – one that exists by effacing the relationship between location and other built structures to attain universality, or to become a timeless, independent creation.

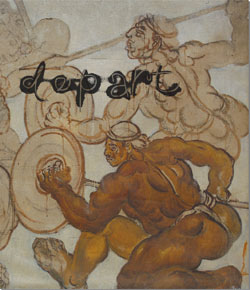

Louis I kahn, the auteur who envisioned this gargantuan structure and gave it its material shape, along with Robert Ventury, at one point in his life, distanced himself from the rigours of formalism which proliferated under modernism's much vaunted International Style. His ambitious building, with its premise on vast spatiality encountered in the Roman ruins shows loyalty to the materials and thrusts towards the sky in the fashion of a European castle with actual moats around it, though in its midst a complex geometry plays out its abstract drama in epic silence.

If Kahn represents the classicist romantic who emerged equipped with a renewed sense of space and construction inspired by the Roman ruins, pyramids in Egypt and the American transcendental thinkers, there are other shades to modern architectural realization where ocularcentrism reigns supreme. With the latter comes a barrage of materials that are applied to the cosmetic advantage of a building, mostly consisting of technologically negotiated use of glass, metal and the pivots that hold them together.

Modern Europe, the birthplace of constructivist and cubist architecture, had also been the epicentre of the Universal Style. And as modernists stationed in all corners of the globe became more and more enthusiastic in capturing the 'essence' of that advance stage of designing and building, some showed and are still showing an unflinching thirst for a streamlined architectural ethos with the configuration of space as the ruling spirit, while others remained and still remain contented appropriating certain trappings that result from the vigorous application of technology to simply achieve modern day posh and pomp.

Dhaka's skyline has changed for the worse with pseudo-structures bedecked in false façades (read, bogus attempts at achieving posh and pomp) made out of tinted glass, clearly setting off a violence of visual nature which most modern abstract(ed) ideas/configurations usually unleash. With superfluous elements as the cynosure of all eyes, some buildings co-opt the most over-used clichés in order to imbue the space they inhabit with novelty. Thus, the efforts in beautification/modernization degenerate into a predatory form of building by mimicking the dominant trend sweeping the 'centre', one which results in an uneven type of patchworks at the 'periphery'.

The two divergent aspects of modernism, one that is chic and not showy and the other that is chic and desperately showy, are often paid homage to by local architects. Embedded in the culture of the previous century, they form the two opposite poles of modern-day designing and building.

The modern mode that reverts back to the primitive, or to the classical, avoids being trapped in any meretricious garb. Yet, buildings realized through similar modes are sometimes adorned with rhetorical elements/devices. The process of denuding the cosmetic layers to show material can be construed as a means to achieving transcendence, thus surface plays a strong rhetorical role by keeping use value at bay. Sometimes, the structural composition itself can push the building towards an über-structure, as in Louis Kahn's grand parliament building in Dhaka.

Conceived as a monument, Kahn's building forwards its narrative through features of grandeur and the play of space and light in the vein of Roman classicism where grand arches are employed to create the cavernous interior which, undoubtedly the most important constituent of their grand spatiality. Kahn encountered Roman ruins during his study in Italy, and was struck by the earthly achievement of such buildings against the celestial aura that Greek buildings exteriorize. Yet Kahn was no simple-minded earthy creature, his ambition to parallel the horizon-expanding vision of the Romans easily united with that of the celestially-inclined pyramid builders of Egypt. The result, of course, was the geometrically complex solutions to volumetric space.

Since there exists no essential indigenous value through which to make a building look well integrated into the given social-cultural or even ecological milieu, how do we develop categories of knowledge to measure the situatedness of art and architecture? The qualitative factors that go into the locational architecture have no fixed frame of reference, nor do they unfold any aesthetic/epistemic indicators explicating the building's relationship to the locality. As in reality this relationship is in constant flux; and from within this indeterminate field of play there emerges a plethora of forms that can easily be detected as locational. But for Kahn, Bangladesh was like a testing ground for his own vision, the people as well as the climatic variables were unknown to him, as such the structures – grand as they are – were built in a way as if they care little about how they would face up to the monsoon rain. Consequently, it seems that Kahn's creation is all about play of light and spatial awareness framed as a grandiloquence simmered in silence.

However, being informed of the local weather or heritage and existing cultural variables are never enough. If one is to look for new aesthetic avenues, one must be aware of the fact that distancing (from tradition) too can be a way of re-organizing one's own strategy to re-engage with a particular community and its inheritance. The creation of a discordant or new spatiality-temporality is prerequisite for the arrival of new forms of art and architecture. And surely that 'new' is known as new in the context of the locality or the world, which may or may not be the result of negotiating the so called International Style.

- DEPART DESK