Features

OGCJM

SHORT-CIRCUITING THE MAINSTREAM

The event is a rupture in the current circumstances (what Badiou terms the state) caused by an awareness of what is missing from those circumstances. – Criss Bateman on Alain Badiou

Outside the regular spatiotemporal matrices of urban design there exist zonalities of difference, or liminal spaces, where one finds oneself by chance or fluke. Situated beyond the map of habitual urban transfer and traffic or interchanges, these transitory nodal points keep emerging and disappearing as if they are glimpses from our unconscious, stoked as they are by the desire to drop out of conventional temporal sequence and need-specific spatiality, where being remains mystified and resigned to the status quo. If Rafiqul Shuvo, a young maverick artist-turned-curator, for the first time, has been able to map a detour with the intent of making the art-crowd step into an alterity of what we usually conceive of as an exhibition space, or a different time zone doped with interactive modalities of art making and related anxiety, he has done so through a duel conduit. First, by setting his stage in the dilapidated part of an industrial zone, or a space in retreat, which is Tejgaon; and secondly, by prepping a warehouse into a factory for artistic inventions as well as mythic projection as a naysayer to the convention. His is an effort in decentering the art scene.

In this temporary exhibition space, cautiously re-arranged to have fitting disposition, the curator intentionally puts salt with sugar, the raw with the cooked and other assortments of flavoured and unflavoured articles, yielding an uncanny mix of some extraordinary, some good, and a few sloppy artistic results. But most importantly, the space/stage is conceived not as a plain repository of objects or bodies, or composite construction that holds in its midst several choreographies, different mise-en-scène loaded with mostly anti-aesthetic virtues and vibes, but as a body in itself – a tableau in its own right.

Amidst a strong sense of iconoclasm that enframes the new space construction, one is able to trace the 'will-to-power' that operates behind such transfusion of existing artworks/bodies and the imported and made for the location bodies resulting from a seemingly random sourcing of art. The list includes artists of various inclinations, photographers, pranksters, a poet and singer, a Bangla rapper and even a Bangladeshi cricketer of international renown.

The mix, where the serious intermingles with the ticklish, the performative or the feverish with the dormant and demure, in the end, makes sense for the re-territorialization that occurred, one which serves to shear the known, mainstream artists off of their shin and provides the rest with an ambiance to be at their self-reflexive best. Thus, Shuvo successfully problematizes the very concept of staging the alternative creating a zone for nomadic practices for a few and a temporary museum for some, thereby initiating multiple encounters.

This extratemporal and extraterritorial threshold – where the space runs into the art and art into the space – makes sense only if one believes that all the other venues of mainstream affiliation and ambition, vitiate, even if to a degree, the intellectual and emotional charge artworks hold in their core. It is due to the fact that most spaces are remote and too anesthetized to accommodate art that rejects 'smug aesthetics', to borrow Allan Kaprow's phrase, through which artworks are often rendered nothing more than an industrial product often verging on the sopophoric.

So, the newly conceived site – the warehouse turned exhibition space – is certainly a concoction of a superior scheme and is reflective of artistically incestuous minds of its organizers. The intention to whittle out a niche for artists who are regularly being made 'othered' by the circuits of mainstream knowledge and spaces, and putting into the resultant mix some unexpected mainstream and non-artist names, to generate encounters within encounters, Shuvo's devising of the alternative in this reconfigured clutter of a maze, a web for one to follow in both loops and tightropes, is an alternative to the existing alternatives.

To look at this very site critically, employing the Apollonian-Dionysian dyad famously introduced by Nietzsche, one is lost in its heterogeneity. One will be hard put to find the ground for inclusion of a couple of overrated names from the mainstream if one attempts to adduce a Dionysian implication of the event. But the site itself seems to have been built to devour all and be merry in doing so. This amalgam of a show, cannily titled OGCJM – Only God Can Judge Me, though well-equipped, yet showcased in a rather low-light atmosphere, gives off a strong noir sensibility. Appropriated from a youth anthem by the late American rapper Tupac Shakur, the title fits the intention of the open-ended construction which, in the end, advances layers of meanings – both congruent and incongruent – from within its cobwebby whole.

We see proper names that stand for outsider paradigms among whom Ronny Ahmmed's visual parables of psychedelic intensity complements the work resulting from the collaging of reality and imagination in Abir Shome's video installation. A brand new talent, Abir's forte lies in critiquing science as the 'truth teller' by way of exploring the conceptual possibility inherent in the (in)human drama science and technology together effectuate. One encounters a demonstration of the futility of knowing, which is apparently a form of consuming science minced into information.

Some interactive pieces make elastic the boundary of art and hammer home the fact that today's artistic innovation may well be a balancing act between framing of the conceptual premise and finding the technological means to reach a satisfactory end. The simple maze that Jubaier Alam builds employs such a technique in which his two toy cars endlessly search for a way out, making explicit the scorched human hopes at the terminal stage of the Capital Age. It addresses the dromological fallouts that beset our social sphere, making us notice how the resultant phenomena have left all trapped in a maze, the analog of which is to be found in the symbolic and fetishized constructions that are the cars, stuck as they are eternally inside the simple, squarish geometry of the maze while we keep 'waiting for the miracle', which is also the title of the piece.

In Md Abdullah al Rana's piece technology collapses into black art – where left-over buffalo bones, actual refuge from the slaughter house, are put on a platter (car tyre turned into a serving dish) and made to sway vaguely imitating a locally-made stationary, yet swaying, taxi ride in a children's park.

Plumbing the Warhol-like 'just look at the surface' kind of visual ethos, some of the participants try and weigh the value they are able to add to a changing discipline by exploiting the photographic, photoshop and fashion syntaxes as a testing ground for idiomatic maneuvering, as is demonstrated by renowned photographer Imtiaz Alam Beg, and artists like Wakilur Rahman and Md Shakhawat Hossain. Hossain frames the body image around slick attires and a head-consuming headgear made of plastic drinking cups – one that actually replaces the head. Wakil, on the other hand, proposes a series of personalities, most with their arms splayed, photographed against the diagram introduced by Leonardo, only to refute the renaissance master's anatomy of perfect human being based on the ancient geometry of Golden Means or Ratio. All three presentations explore Western aesthetic parameters in their obtrusive and unobtrusive registers.

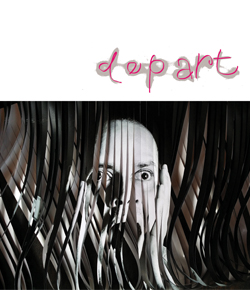

Though text arts abound this show, one by Raihan Ahmed Rafi seems to be informed by linguistic philosophy. In it a video work displayed on a monitor placed on a high-stool shows a tightlipped mouth where words run in horizontal cue upon the closed lips as if to demonstrate the fleeting nature of oral construction. Seen in the light of the concept of 'linguistic man', to draw on Agamben's formulation, a human entity that continuously builds and rebuilds him/herself through various pronouncements – prophetic or otherwise. The work recreates the orginary scene with a text proposed as text-defining text, which he titles Mark My Word.

In another conspicuous jumble of a piece created as an homage (by the curator himself) to late Tarekuzzaman Tarek (1994-20120), we see threading of a series of stills and exchanges sourced from the Facebook, while, another participant, singer and poet Arup Rahee, through his sequentially placed studio photographs of himself in three stages of his youth and other references to his past in the form of personal letters captures the unstable nature of our social subjectivity. Three self images in passport-size format are put in chronological sequence spanning the last twenty years of his life with the first one dating back to 1991, taken during the SSC exam, also the year of graduation to manhood.

The photography genre is often intentionally made to wear a second skin or should one call it a process of revitalization of the genre through poetical means; and none other than Shumon Ahmed, a renowned exponent of photo art, tackles such a mode with considerable acumen in creating an 'intertext' while sticking to his own brand of stream-of-consciousness images. Ambiguity is what he achieves in the piece Destination, focusing on the site of embarkation, and on-flight moments and lastly on the destination reached, and all in a seemingly passing but a deliberately overpowering manner. As his still images as well as the moving ones in a video stream toggle between contemplation and surface-level surfing, they together construct a visual poetry by threading the moments of inspiration, despair and most importantly, oblivion.

Among other interesting entries, there is a series of illuminated idiot-box-like constructions created out of discarded cardboard-box and titled Magic Box: What We are Watching, which is artist Abdus Salam's invention. Constructed as a collage of moving images cleverly using the simple method of shadow theatre, each of the TV-like boxes is lit from the inside and is made to produce a replay of moving, swirling series of signs as a commentary on modern-day delirium and stasis. But it also has a poetic, childlike aspect to it, though the real TV monitors that share space with the make believe monitors only serve to highlight the contrast between two divergent technologies. A Rahman, in his photographed mirror, captures the city in fragments, using a playfully torqued idiom, to divulge some unattended helms that lie scattered around Dhaka. His work too does not preclude the visual poetry that tones his thematic while the reflected objects are made to abandon any subjective emotion.

A collage of a sculpture by Mizanur Rahman Sakib titled Jump – where a popcorn smothered male mannequin and an awkwardly propped-up car jutting out from the side of a popcorn mound come together to form a monument to our speed-obsessed age – shares space with a quasi-art object of an orangutan statute placed amidst a heap of bananas laid out in a circle, bearing obvious signs of self-indulgence which one may or may not find teasing. Such cohabitation seems to provide OGCJM with two focal points – one that calls attention to the current trend of aligning the street with the exhibition space and the other of the failure of some to transcend the object as prop to arrive at art proper.

One important portal to backlogs, which the site opens, serves to reestablish our link with some artists whose works have become known for their absence – be that a long or a short one. Artist such as Salam Abdus, who had been active in isolation but had ceased to show his works at mainstream venues since the mid 1990s, enjoys a happy comeback with extraordinary modernist take on human condition; Ali Sagar, a young exponent of outsider art presents a series of paintings where the poetical meets the kitschy; and Kaiser Selim, a self-taught artist who paints as part of psychotherapy, gets a fitting treatment as a series of smallish oil works representing his mental states form his display.

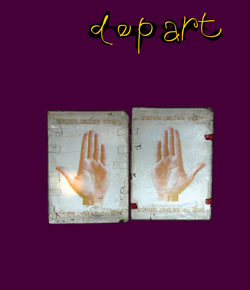

Apart from a few seemingly unattended props, the OGCJM site has been pregnant with some exceedingly welcoming pieces of junk and/or art that juxtapose images, objects or electronic devices and other self-propelled acts with varied results. The visually absorbing panorama by Swarnali Rini; the Iron Rain canvas by Marzia Farhana, where she literally translates the concept of rain into falling iron; the self-examination with a self-destructive attitude in Shuvo's doctored photographs of palms devised in a sequence where in each piece one finger is cut and readjusted as if the artist is treating the body parts as collage materials; the trash bag-like construction filled with dolls by Mahedi Anjuman; make one push for the elimination of the distinction between high art and low art, which in turn, produces a statement – an aesthetico-political one – in hi-decibel note, with the intent to be heard across the art scene of Dhaka, where a plethora of new breeds of art remain undertheorized as does the mainstream dross.

The wit and the psycho-social implications aside, this site that readjusts the foci on, and reset the stage for, the alternative art, is in need of hyperintellectual actions to be able to delineate the jump from the 'content-level perception' to the 'process level perception'.

Against the mainstream monoaxial modality of freighting art which more and more falls into the category of modern terminus (in

Bangladeshi context, of course), OGCJM constructs a jazz or a multi-referential event comprising mostly of involuntary emotional and intellectual acts. Compared to the main venue of the Shilpakala Academy during the Summit, where a greater part of the display can clearly be recognized as the teleological end point of the prosaic mainstream traditions, at OGCJM, notwithstanding slips and falls it too is afflicted by, things are such that this multiform exhibition signal's a new beginning.

OGCJM was held at the warehouse of Circo Soap Industry at Tejgaon, April 11-15, 2012.