close look

The Poetics of Political Art

Somnath Hore in Retrospect

Somnath Hore (1921-2006) is one of the most prominent figures among the pioneers of modern art who, by injecting a strong sense of disillusionment in the social climate about the capitalist circulation, once sparked reassessment about art and its social function. Strengthening the strand of cultural streams that looks social ills in the eye, Hore ensured an important niche in the history of the twentieth century development of art in Bengal. Similar voices had emerged before him, and also after him, yet as an exponent of modernism Hore articulated a position vis-à-vis art framed as a critique of the social order, first by focusing on the masses and their struggle for emancipation and later by voicing discontentment about the given social matrix as well as evincing the human predicaments in its midst.

Somnath Hore (1921-2006) is one of the most prominent figures among the pioneers of modern art who, by injecting a strong sense of disillusionment in the social climate about the capitalist circulation, once sparked reassessment about art and its social function. Strengthening the strand of cultural streams that looks social ills in the eye, Hore ensured an important niche in the history of the twentieth century development of art in Bengal. Similar voices had emerged before him, and also after him, yet as an exponent of modernism Hore articulated a position vis-à-vis art framed as a critique of the social order, first by focusing on the masses and their struggle for emancipation and later by voicing discontentment about the given social matrix as well as evincing the human predicaments in its midst.

At the very onset, Hore had set himself apart from the rest by being factual as R Siva Kumar points out dwelling on the artist's early years. In a write-up for the book that marked the retrospective show at Santiniketan, Kumar argues that the emphasis was never on rhetoric as was the case with Zainul.

As an active member of the Communist Party of India (CPI), Hore, at the onset, developed an oeuvre consisting of 'portraits of peasants, workers, their secret meetings, acts of resistance, and everyday life' and by 'asserting their humanity with quiet heroism', (my italic) to borrow Kumar's word, the artist aligned himself with the working masses. Kumar also adds that, 'Inspired by Zainul, he set to improve his representational skills,' and the result was evident in Tebhaga and the Tea Garden Diaries of 1946, executed during his second and third years in the art college.

If the zeal for articulating the aspiration of a people eager to see a political change marked his early phase, the later phases exteriorized an effort to align his discontented self with the representational techne of the Parisian avant-garde. The multitudinous ways of voicing the social and the conditioned or trapped social subjects in its midst, have made Hore's oeuvres worthy of recounting and reframing through sympathetic gaze and hindsight.

Many of his compatriots were either inclined to see art as mere activism or as a depoliticized site for 'pure' aesthetic action. What is more important is that he is one artist who could distance himself from his art by being self-critical, which indeed is a rare trait in the context of our art history, and this very trait has been crucial to its development as multimodernism.

Even the political turmoil that gripped West Bengal after the two splintered factions of the communist party were at loggerheads in the early '70s, spurred the erstwhile member Hore to find his markedly individual voice to tackle issues related to society and art. It was in 1956 that Hore decided not to renew his membership in order to distance himself 'from the crass material politics,' to use his own word.

He was never skeptical about class struggle, neither did he ever lose his faith in socialism, what he was disillusioned about is the crassness and degeneration that went hand-in-hand at the grassroots-level in Indian politics. As for his own art, even towards the last days of his life he expressed doubts about his position as an artist who harboured a strong desire to attend to the social reality with the zeal of a socialist, but by drawing on a paradigm which connects him to the early twentieth century European avant-garde. In an interview to Matiur Rahman, he once said, 'Probably I am suffering from middle-class romanticism, and have never tried to go beyond it!'

One may face an important query after his death in 2006: why this sense of doubt afflicted him after years of relentless art-making which resulted in the oeuvres of various political, social as well as personal ambition as he explored multiple means of painting, sculpting and making prints? The answer to which can only be found by predicating his thoughts upon the principal bedrock through whose mediation he transported his art into the public domain. In kolkata, left-wing ideology easily married Sartrian existential introspection and the sense of uncertainty it gave rise to, therefore the subjectivity on which a greater part of artistic productions were premised was that of an alienated individual. It had shaped his art throughout his life; it also made him doubt the effect his art produced on the spectators.

To gauge the success of a master of Hore's caliber one must survey the socioeconomic context of his time and the art that preceded the surge of modernism in the then undivided Bengal, and, additionally, one also needs to be informed of how modernism in its most reductive and linear form has been only a surrogate to the European modernism.

In the second half of the 18th century, Romanticism swept the art and the cultural arena of the west, while, conversely, in the social sphere the industrial revolution was underway. In many respects such movements towards transcendence of the social reality depended heavily on the changing social relations that manifested in various forms of class as well as creative struggles.

Looking closely at Hore's oeuvres, we find a plethora of expressions suggestive of the inability to translate the political will into reality; but do we see the implications of 'utopia', or the urge to construct a classless society? Put another way, was Hore able to articulate the gestation of a dream that so many in this part of the world was affected by, or was he an artist who could only focus on the fallout zones of the bourgeois social milieu, which we have finally accepted as fait accompli.

Perhaps he was caught between the urge to establish a classless society and the catharsis sparked by the very act of art making, which he used to consider as a way to give vent to the collective/social desires. The fact that his longing for an ideal society remained unfulfilled also impacted his language of art. His imagery began to look either more fragmentary or devoid of representative elements. What Alain de Botton calls 'Infalicities that corrode ordinary life' is what in Hore's paintings, print and sculptural pieces assumed a certain contour and character inscribing the otherwise innocuous surfaces with a sense of disquiet.

Yet, it is a fact that he saw art as the manifestation of generalized emotions where the collective unconscious determines the social goals while the individual keeps exerting his/her influence over the nuances of thoughts and forms of expression. And it is in conjunction of both the worlds – the collective and the individual – that an artist's voice is form.

Thus the scope is created for mass utopia or dystopia to find an expression in a strong individualistic style. If the reading of communist texts allowed for the artist to become aware of the social structures and the individual's place amidst the grid, it also spurred him to question the individualism which we may easily connect to European humanism that sprang out of the Enlightenment, which, subsequently led to the formation of the current global capitalism. Hore's position resulted in a language which is at once fraught with the individual's craving for an exploitation-free society and is also seared by the failings of an entire population.

Modern aesthetic discourse has many different strains in this clime, though we often encounter the individualist-socialist dyad as a major topic irrespective of the fact that it has, over the last few decades, entirely lost its cache. If one is to clarify the kind of social engagement artist like Hore once achieved, the argument can be redirected towards a frame based on the holistic-individualist dichotomy. If the former sees the art-life nexus as ever-evolving matrices through which the individual finds one's place in the world, the latter seems to be hinged on an individuality that seeks to establish a distance from all matters social. However during Hore's time, the discourse of modernism had been bogged down in even a worse kind of mire as the debate centered on the false dichotomy framed arround the concept of art for art's sake and art for life's sake. It seemed the most pertinent issue back then, and in relation to such a dyad he was on the side of 'life'; though, from the present perspective, he can easily be seen as an anthropocentrist given to the dehumanizing representational techne.

The basic foundation of anthropocentric philosophy or art for life's sake lies in the political, idealistic and moral strands of the Bengal Enlightenment era of the mid-ninetieth century. But what makes Hore distinct from other artists of this loosely defined humanist-socialist band of progressive urban intellectuals who actually had never belonged to any particular school of thought – that he, in his own manner, could sidestep the simplistic interpretations of a complex situation. He did so in order to stand on a turf where the social man is also overwhelmed by the individual's thirst for a de-social, de-iconic expressivity. And this is exactly where the dehumanizing representational techne comes in and sinks its teeth.

Retorting to a question framed around art and politics Hore once said, 'Socialism is the social consciousness earned by the exercise of one's innate cognition. Artistry on the other hand is the special ability that one is born with. Socialism may well encourage an artist to create works of art, but it can never make him an artist.' The artist Hore knew the limits of the marriage between his political ambition and the artistic vocabulary.

The exhibition of Hore titled Khato (wound) at the Bengal Gallery of Fine Arts, bound to spark reassessment of this ardent socially-inclined artist who knew that art and politics could only share ceratin thresholds but can never be one. Social consciousness, Hore believed, is behind all great artistic traditions, and 'aesthetic revelations' is the central force behind all great talents.

From within the aesthetic space, the social emerged to Hore with all its inconsistencies. From the linguistic point of view, khato is a word which signifies an atrophied reality connected to the artist's historical experiences in the human induced famine and in the spates of communal violence leading to the partition of Bengal. Social consciousness is tied to the fact that social reality and its structure is not of nature's creation, since nature does not mediate social life-events or subjectivities, and what gives rise to this psychologically and socially loaded word which is 'wound' is when the body-self-psyche that is scarred as the result of the aberrant, deformed body politic.

The works that are brought together in the current show are like indices of a soul searching for an array of languages to freight the dystopia following a series of debacles, including the failure of the communist movement(s) in the first half of the twentieth century in India, which in turn gave rise to the Naxalite movement, which consequently was another big failure. The vacuum in the collective social psyche can be traced in Hore's art as early as 1971 when he embarked on his paper pulp print series entitled Wounds.

The linguistic construction Wound, which is the thematic of a particularly interesting series of work and the title of the current exhibition, is the result of the conflicting elements in reality. Question might arise as to the nature of this conflict, the origin of which lies in the historical and social consciousness leading to the formation of an utopia, or dystopia, which consequently makes one question the current order. In Hoar's art three aspects of the social and the temporal are very important: historical perspective, political ideology and the aesthetic zeal connected to the European avant-garde. In the centre of these three he situates the human he wants to represent, who, in Hore's techniques, after his communist-activist phase, is not a wholesome, or complete human being for that matter. Hore's humans are always deprived, oppressed, diseased and distressed and are often pushed to their limits.

To understand such a forlorn condition, a historical consideration of an artist's position or identity vis-à-vis the oppressed is necessary. Following the rise of psychoanalytical and behavioural psychology to prominence, we know that one's identity is connected to several determinants: nationality, religion, race and language. In an authoritarian age, with the multinational army having imperial ambition, these personality traits translate into social orders and manifest themselves through different guises: sometimes in the guise of democracy, sometimes humanism, religion, race or nationalism. But Hore's own identity cannot be found there, it must be sought in how he developed into an artist of social engagement who antagonize the status quo.

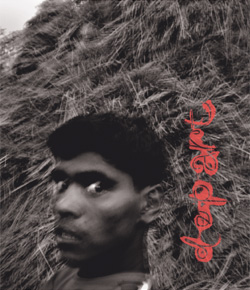

He was born in 1921 in the village of Barama, Chittagong, during the British Raj. Having grown up there, he did his Intermediate of Arts (IA) from Chittagong College in 1940 and got admitted in the Ripon College in Calcutta (now Kolkata) the same year. Apart from institutionalized education, his initiation into fine art began at an early age. He learnt the basics from the Medenipur artist Chitta Prashad Roy, a left activist known for his empathetic portrayal of the masses.

However, the mixture of angst and historicity we trace in Hore's paintings has two springboards: one is the Second World War and the other is the Bengal famine of 1943. When Calcutta was smarting under the Japanese (air)force in 1942, he was forced to go back to Chittagong, his birthplace. Chittagong was struck by a gruesome famine the following year, as was the entire region of Bengal. It was at this juncture that he became involved in the communist movement as he volunteered to be engaged in relief distribution. The party commune became his home. At this stage he worked on numerous paintings which he later showed in subsequent exhibitions. The party newspaper Janojudhya or 'people's war' regularly carried his drawings, posters and paintings. In 1944 comrade Bhabani Sen invited him to Calcutta and asked him to operate from that city as his base. The following year, he got admitted to Calcutta Government Art College, mostly on the insistence of the famous communist leader PC Joshi. He spent four years in close companionship with comrade Muzaffar Ahmed and Bankim Mukherjee. Therefore, we may conclude that he grew as an artist and individual riding on the wave the tumultuous history of the communist movements in the subcontinent. In that sense he is a witness to and a participant of epoch-making events.

The historical development of nationalism is also one of the key factors in his paintings as the anti-colonial patriotism served him as a mirror in which to reflect his individual identity as well as the collective disillusionment he sensed pervading the social sphere. As an artist driven by political ideology (Marxian philosophy had a deep impact on the artists of this region in general) he shaped and reshaped his language in lieu of the social decline and the rise of the Capital Order.

If one considers the fervour of the middle-class romanticism that once made them choose to align themselves with the idea of social revolution and change, one clearly sees that the struggles, though driven by genuine intention, finally hitting a wall which the leftists of this clime could never topple – both in the epistemic sphere and in reality. Hore's self-confession about his own painting in an interview mentioned earlier is a testimony to such failures in the arts, one which undoubtedly echoes the failure on the level of real polity.

The faces of the hungry and the oppressed – the victims of a human induced conditions – are the references through which we stand witness to the dystopia. In terms of form, the experimentation which is a consequence of the encounters with the European avant-garde, what proliferated are viable modes of confrontation with one's own society. This fraught language helped Somnath Hore to carefully sidestep the naiveté that afflicted the middle class in their aspiration to form an ideal society. As such, art as a register of social life found a fountainhead from where all those angst-ridden, emotional transmissions were made to flow.

The Cubist-Expressionist contours and characters that filled his art spaces, though actually a throwback from the early twentieth century Parisian avant-garde, they were a way for Hore to plumb the depth of despair one is often struck by in a climate where exploitation is the rule. The emotive force that guided him, helped generate other nuances – ones that are by far the most distant cousins of expressionism or cubism.

language (of art, literature and everyday existence) is the refuge of the body. Since language can take a shape similar to that of the body, language also produces the body – helps it to make appear. Thus in Hore's art the fractured elements of his language captures the body in a splintered state which is otherwise unattainable.

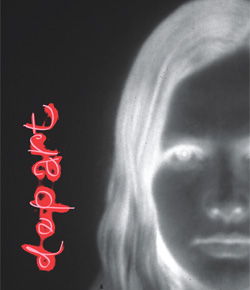

In the realm of the politics of language, body in this manner is at once transgressed and transformed. In Hore's language, for its capacity to embody and disembodied material truths, one notices the hunched and fragile bodies, fragmentary and disappearing bodies to initiate that transgression and transformation. The lines are made intentionally wavering. Through such subjective means or emotive tools, he, perhaps, wanted to manifest the 'wound' as the embodiment of the given reality. And this is no clement reality, it is rather a landscape troubled by colonialism and the rising bourgeois ambition of the local rich and the cognoscenti on which the artist critically reflected. Yet the humanity/community Hore constructs in his artistic domain, takes the form of alienated, vulnerable individuals.

Most of his figurative paintings, therefore, manifest the consequences of a society divided by class. One cannot find any utopia here; rather a sense of dystopia prevails as it portrays man's frustrated hopes and aspirations. Although his form resembles that of the cubists, expressionists, or even to an extent, German dadaists, the individuals he represents are of the trampled or struggling people of the subcontinent. This is precisely what makes him unique.

In some of the early works, where the faces or the figures still have not disintegrated into geometrical fragments, they look melancholic amidst the half-light, half-shadowed areas of the paper. The melancholy of the image cannot be explained only by the framework cast around the word 'wound'. It is not clear why his art should be titled as such in general because wound is only one determinant of modernism. Other determinants are also very much present in his art. Therefore, the title only undervalues the oeuvres he produced over the span of 60 years – from the mid 1940s to 2006.

Interestingly, to understand this point, the prints in the white on white series can be of help. It captures the forlorn reality in such a silent manner that it almost transcends the reality (of the artstic space and the society) and pushes the viewers into a neutral/neural, a-historic zone. About his Wounds series he once wrote, 'The ruts left on the road by wheels, the cuts from the axe on the side of the tree, the injuries on the human body left by weapons – to my eyes, they all appeared to be wounds. It was out of this concept of the wound that my white on white works were born.'

The Bengal show produces the opportunity for a survey of this master, and this homage seems to carry forward the idea of art as an evolving site one that is connected to the changing realities as well as psychic spaces most urbanites are forced to deal with on a day-to-day basis.

Translated by Farhana Susmita

'Wound' was presented at the Bengal Gallery of Fine Arts, 25 November-4 December 2011, Dhaka, and at the Institute of Fine Arts, Chittagong University, 10-15 December 2011, Chittagong.

Reference

- My Concept of Art, Somnath Hore, Translated by Somnath Zutshi, 2009, Seagull Book, Kolkata, India.