navigator

Animism in the time consumerism

Joya Sherin Huq's latest coup, where she lets the portrayal of femininity share space with that of objects, attires and paraphernalia that make up the urban semiosis of appearance and fashion statement, freights the viewer into a semi-fantastic and textually circuitous world infused with a strong sense of animism. The idiom that hinges on a rather fragmented pictorial scheme – where the aforementioned elements commingle to forward a narrative that, on one level, traces the collective neurosis – seems both tongue-in-cheek and gender-biased.

The woman in her speaks to express not only discomfiture, as is the wont of some local feminists, but does so in the hope of forming a stream of responses to the puzzling reality of living in the times of (mis)communication. Joya forwards a critique of the world she observes in its everydayness by resorting to a mock serious approach and an unapologetic mirth.

Employing the non-sequitur in the revival of our primordial way of looking at the world, Joya lets parrots inhabit a blue gown, as in Birds with Birdcage; zebras to effect a change in the patterns laid out on a hose while the legs donning two different hoses precariously dangle over a number of red apples in Performance-2; or, an entire animal population of a jungle invade a huge terrace where a giant, shy girl-child smiles from behind a banana tree holding what looks like a fantastically coloured, oversized marigold in Spacious-1. The arbitrary juxtaposition of images only seems logical when one wakes up to the primordialist vision of this 30-plus artist. It seems as if Joya is trying to script a return to the world before it was afflicted by knowledge that always seeks to bring to it a semblance of order, an attribute never to be found in the real world.

The images she employs are intentionally made to look a bit incomplete. Some are developed through her own encounters with herself and a gradual understanding of her place in the world, while others are culled from text books or books of nursery rhymes and modern day stationery, such as, stickers.

This trait of achieving a sense of noncompletion is taken to the level of linguistic playfulness in a set of works including her major entries to this exhibition, From Sanchi to Rodin and Unreal Story. In both, one is accosted with a vast expanse of space untreated by paint. Only the contour drawings are left for the viewers to faintly remind them of an array of elements such as flowers, boots, pistols, fishes, lizards and other animal forms, notwithstanding an aero plane or two. Some of them appear complete, some half-done, and a majority are left unpainted as if to allude to an image- saturated world where overproduction has led to the creation of a self-referential web from where the real has evaporated.

The ultimate irony of living in the world infested by production centers – both virtual and real – is that the actual or real has been pushed to the periphery.

If the artist has no specific commentary on this condition of virtuality, which Jean Baudrillard once famously defined as 'the loss of the real,' it is because Joya enters the domain of representation with the stomach of an omnivore, appropriating all and sundry in one broad sweep. Like the European Surrealists, she is interested in everything around her, often choosing to stage the act of painting over and over again to prove that the magic or joy of 'being in the world' clearly is the source of all meaning.

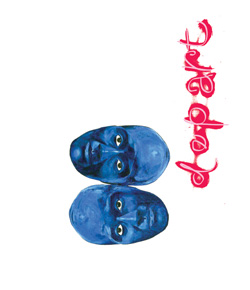

Joya homes in on the fact that life and meaning exist in a relational framework. So the texts – in the form of image production and linguistic narration – we as human beings keep generating, can never be assumed as having a fixed meaning as they are meaningful only when placed in a relational matrix. In her hands, the Doremon dolls (a Japanese comic character) that have flooded the market transform into an imposing object with a totemic spirit otherwise dwarfed in the age of overproduction. With this one in view, one is able to grasp the discourse of this artist which is based on an animistic interpretation of the goings-on of the market-driven society. Sameness and simulation are harped on in her work alongside the unveiling of a world of relationality – one that goes beyond the material understanding of the self and its place in the world.

The exhibition entitled All Dressed up and Nowhere to Go frames an ontology of the world rather than a representation of it in codes, these codes despite yielding to multifarious decoding persist as part of a meta-reality. Joya falters in works where her elements are not open to interpretation, as in Aquarium.

Joya's success lies in that, instead of a misbegotten journey into a world of appearance, she lays bare a world full of recontextualized objects and animals, which include the human animal, to make explicit 'a relational web through which life's irony, loss, happiness (…) with the desire to transcend the physical limits,' to use her own words set forth in her statement. This is the project of a woman inclined toward remapping visuality in relation to an animistic vision to ritualize the artistic space – in the contemporary context, of course.

The exhibition All Dressed up and Nowhere to Go was presented at Bengal Art Lounge, 15 February- 3March, 2013.

GOLAM MORTUJA is a freelance art writer based in Dhaka.