Features

Vastukala : The Architecture of Muzharul Islam

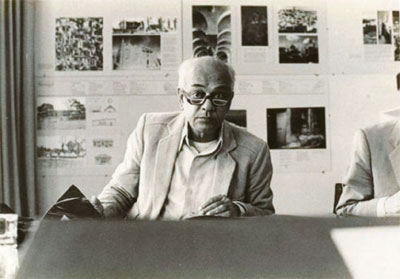

Muzharul Islam, the master architect who passed away more than a year ago, was not just a modernist, he was modernism, a single man representation of a national destiny. From its tentative beginning in the 1950s to its proliferation at the present moment, the life and soul of modern architecture in Bangladesh was moulded by the energetic spirit and vigilant intellect of Muzharul Islam. This has been said by many, and I myself have said it many times while opening an essay or article on him that he singlehandedly brought modernism to Bangladesh. Now, especially a year after the passing away of the architect, that oft-repeated mantra is understood with a greater poignancy and meaningfulness. If only in death can a greatness be revealed, an appreciation of the immense contribution of Muzharul Islam has not even begun.

In a true spirit of the Bengal Renaissance*, something that defines the work of Satyajit Ray in film and Jamini Roy in painting, Muzharul Islam took on the enormous task of creating a modern yet Bengali paradigm for architecture. Somewhere between the idea of an uncompromising sense of a Bengali nation and the practical matter of the building arts, Muzharul Islam was active in defining the scope and form of an architectural culture. 'The people who first started here had their source in an incredible love for the country,' Muzharul Islam would remind many, 'The basis of the movement was: I am a Bengali, I have a language, I have things to tell my people, I want to build a decent society, everyone in the society has the capability and the right to what is available in it.'

Consequently, modernism was more than an architectural language or aesthetic operation for Muzharul Islam; it was an ethical and rational approach for addressing what he perceived as social inequities and cultural gaps in the country then. His Marxian principles combined with a Rabindrik ethos in creating a challenging, and almost impossible mission for himself. His steadfast commitment to the modernist ideology stemmed from an optimistic, even utopian vision for transforming society. At the same time, his deep sentiment for Bengali culture did not dissuade him from pursuing the goals of a 'world man.' 'I have always repeated that one needs to be a Bengali,' Muzharul Islam declared. 'One needs to be a world man. You have to be a world man and a Bengali. It's impossible otherwise.'

Muzharul Islam does not offer an easy access to his world. Firstly, while his architecture owes much to the language of modernism, there is a more complex relationship with modernity. Secondly, his buildings, not produced for photographic purposes, are more than what they appear; they are organizational and constructional. Thirdly, the buildings constitute only an aspect of Muzharul Islam's broader relation to architecture culture. This includes his role as teacher, mentor, activist and often the provocateur. This is further complicated by his political consciousness and, since the 1970s, by his direct political involvements, spilling the scope and substance of architecture beyond its conventional boundary.

Architectural modernism might have begun in Bangladesh with Muzharul Islam, but modernity has a long lineage and deep stratum in Bengal. Muzharul Islam emerges from this and it is against that, that his output can be situated. It is, however, necessary to rethink the relationship beyond the demonization of modernity which characterizes most contemporary architectural criticism. For most Asian societies, modernism is often conveniently seen as the perpetrator of cultural ruptures, pitting it against a 'pre-modern' condition, that is, tradition. The reverse claim, present in the work and thinking of Muzharul Islam, needs to be examined too. It might be seen that Muzharul Islam adopts and employs the principles of modernity in order to overcome what was perceived as colonialist rupture. Modernism, in this sense, becomes an attempt to 'return home'.

How do we enter the twenty-first century?

The oft-raised question, posed by Muzharul Islam, throws one immediately in the throes of modernity. The generality of the question leads to more concrete reflections: on the idea of the nation ('we'), on the political and economic nature of society, and on its spatial manifestation. One also senses in that query a degree of hesitation, a momentary stalling. The question, as much as it is about propelling forward, takes in by that hesitation and that collective 'we', a glance at the other direction, the past. All the issues that recur in Muzharul Islam's thinking are in this query: what to hold on to, what to abandon, what to take.

The idea of modernity in Bangladesh, and by extension the ideology of Muzharul Islam, can best be understood by that broad sweep of cultural and intellectual upheavals ushered in Bengal by the 19th century movement often described as the 'Bengal Renaissance'. The movement, the basis of modern Bengali society, was a complex intertwining of acceptance and resistance; a resistance to both the traumatic experience of colonialism and the tyranny of tradition. The condition of acceptance was also two-fold but more complex: it involved an outward voyage to embrace from a global repository anything that assured a new degree of social and intellectual liberation (as for example, the scientific, progressive and humanistic institutions of Europe seem to promise), and, an inward journey, a conscious 'archaeological' excavation, so to say, of one's own uncharted and taken-for-granted cultural stratum.

The inward journey involves the process of understanding oneself. This is important, for this implies that one is suddenly made aware of oneself, and, as often understood, self-awareness is double-edged: it is a moment of self-discovery, it is also a moment of a distancing from the familiar. The search for self-discovery presupposes a sense of alienation and remoteness from tradition and does not arise so long as, as the Indian philosopher Jaravalal Mehta comments, 'we unreflectively live under its domination, or fail to see the novel present as it actually is and claims us.' Both Charulata and Bimala, characters from two Rabindranath novels, beyond the gender issue, signify that at the moment of self-awareness the familiar is made foreign, or conversely, one is made a stranger to the comfort of familiar settings. And, yet, it is within this condition of self-awareness, where tradition is no longer available unreflectively, that the idea of identity – cultural, national, or whatever that may be – can arise.

In essence, it is this paradox which creates the project of return home. 'Return home' is a metaphor, even if an exaggerated one, by which we can name the struggle encountered particularly by the 'Bengal Renaissance', the movement to articulate an identity when tradition is no longer available uncritically. This leads to, on one hand, the appropriation of foreign ideas in the very core of society, and, on the other hand, to zealous, often over-zealous efforts to resolve what it means to be Bengali. As often, the words of Rabindranath Tagore poetically encapsulate the Zeitgeist: the inevitability of the journey, and the exilic anguish of departing. In 'Probash', Rabindranath speaks of the thousand bonds binding one to the ancestral home (bhita). Yet, he realizes that 'the vast universe is beckoning me from every shore/there is a thousand knock of the world at my door.'

It is by way of attempting to 'return home', and not by a stylistic or a rhetorical motive of progress and development, that one could best approach Muzharul Islam's alignment with modernism. This encompasses the work, the political commitment and the personality of Muzharul Islam.

What is the historic root of this alienation from 'home', the point of departure, so to say? In Muzharul Islam, the question of 'return' emerges because of the colonial experience, through interpreting colonialism as a “rupture,” as a fatal and irreversible condition created by its disruptive mechanisms. In the context of Bangladesh, the 'rupture' is compounded, since the time of Pakistan, by the added pressure to undermine 'Bengaliness' by a pan-Islamic ideology. These disruptions positioned Muzharul Islam to speak of 'mone-prane-karmokande khati bangali houa,' that is, to be a 'true' Bengali in mind, spirit and praxis.1 This is another sense of the 'return' metaphor, taken up particularly as a political agenda, that one is displaced from where one was once mone-prane-karmokande Bangali, and the return to that site prior to any ethical and creative behaviour.

Modernity, for Muzharul Islam, was always as much a returning as going away. It is a going away from the immediate colonial past, and a returning to an 'essentialist' condition which seems free from specific religious ideologies or traumatic heritage. It is this which might distinguish it from the radicalizing motive of European modernism. For most Asian societies, colonialism is still the critical datum. When Franz Fanon speaks of 'defamiliarization' as the immediate project of postcolonial culture, it is not difficult to see why modernity was adopted with such ease. Muzharul Islam wished to use modernity as a way of critiquing colonialism, particularly what he saw as the nature of colonial 'rupture', and to use architectural modernism, as the term suggests in its formal and spatial characteristics, as a way of overcoming the rupture. The rupture cannot be overcome by the adoption of traditional motifs even if it helps partially. Much as he was politically avowed to a Bengali identity and a suspicious of Western domination, Muzharul Islam did not transfer this immediately into architectural making. It is this overcoming, which is not to go away further, but to go forward to an essentialist condition encircling both the past and the present, which may be understood as the metaphor of 'return'.

But, one can no longer return to what once was. Actually, one can no longer know what was. Overt traditionalism, in most cases, is a sentimental return hiding behind it is a consumerist intention (as in the interior decorations of five-star hotels) and a lack of critical and intellectual rigour. Or worse, traditionalism could, and does, slip towards national chauvinism.

There is no longer the return. One can only return critically, there is only a transformed or a 'constructed' return. Once self-awareness begins, we are forever fated to a 're-construction'. But what distinguishes this construction from the facile method of instant traditionalism? What might give the former a greater degree of authenticity?

It is this: Muzharul Islam's position has been dialogical and dialectical. Although hinged to a specific place – its socio-cultural milieu - it did not falter in engaging in a 'world dialogue'; it was also not daunted by the thought that such engagement might necessitate a different, or worse, a new way of making. Muzharul Islam wished to operate within the nexus of cultural particularness and the humanist idea of 'the-world-as-my-village.' This is what brought him close to a Rabindrik ethos, and to the central tenet of the 'Renaissance' movement.

Architecture and nation-building

The American architect Stanley Tigerman, who has been a close friend of Muzharul Islam, related how he found Louis Kahn very disturbed when they met at Heathrow Airport in 1974. Tigerman was on his way to Dhaka for the Polytechnique projects, which he was designing with Muzharul Islam, and Kahn was going back to the United States from India (and to his tragic death). Tigerman recalled that the only thing that was bothering Kahn was the thought of Muzharul Islam and 'how could he leave architecture for politics?' Kahn conceded that he could never do that, and yet, as Tigerman recalls, did not seem relieved by his own statement.2

To begin to understand this is to be lead to the problematic juncture of architecture and nation-building. This is highlighted in Muzharul Islam by two strands of inheritance: the Rabindrik and the Marxian, in other words, the contradictory commitments of artistic detachment and political engagement. While Marxism would tend to flatten out the topography of cultural differences leading to ideas of a radical humanism, Rabindranath would universalize a local experience such that reading lines from his work would make a WB Yeats quiver on a London omnibus, or a Victoria Ocampo weep in distant Brazil.

In Bengal, 'aesthetics' and the idea of nation have always constituted a critical (and problematic) intersection. In fact, the articulation of the nation may be understood, and the political and cultural history of Bangladesh may be made clearer, by bringing up the debate on 'national' style in aesthetics. This took place from the 1900 to 1930s as a direct outcome of the 'Renaissance' movement.

The most vivid record of the triangular tension of tradition, nationalism, and modernisation is seen in the development of 'modern' Indian art. It was primarily through the writings of E B Havell and the work of Abanindranth Tagore that art becomes a site for nationalist discourse. Abanindranath's work was seen by critics and his supporters as the rediscovery project of the aesthetic ideal of India. The implication was broader; it was no less than the political project of national rediscovery, it came to symbolize the recovery of tradition and lost identity. Through the Havell-Abanindranath discourse, art – Indian art as well as Indian ethos – came to be regarded as 'essentially idealistic, mystic, symbolic and transcendental.’3

Abanindranth's attempt to forge a link with the Mughal miniature schools, and later, Japanese and Chinese traditions with a view towards 'aesthetic and national recovery' was countered by two other camps. One was the academic tradition, which in the name of progress as understood through colonial training, was content with realistic rendering of Hindu mythological scenes.

The third position attacked both the pro-colonial academism and the pathos-filled 'national' art of Abanindranath. They were suspicious of the Hindu exclusivism of the academists, but more than that, they were suspicious of both the pretentiousness of 'Indianness' and the exclusiviness of the ideal and spiritual art as envisioned by Havell, Coomaraswamy and Abanindranath. Various thoughts can be claimed as forming this third camp: from the historian Akshay Maitreya who had said that just by painting in India one does not produce Indian painting, to Benoy Sarkar who, writing from Paris in 1922 in his path-breaking essay, extolled the necessity if not the inevitability of a 'truly international modern style of art.' The exhibition of the work of Paul Klee, Kandinsky and other German artists organized in Calcutta in 1922 by Rabindranath and Gaganendranth was a major event. Furthermore, there emerged a group of younger Calcutta artists who declared in their manifesto that the 'Bengal School paintings lacked vitality and that the false sense of Indian art and the propaganda for the eastern art should be resisted.' These artists were referring to the idealized, but sentimental themes of Abanindranath, and also to the more politically-motivated programme of a pan-Asian ethos urged by the Japanese writer Okakura and Sister Nivedita. The analysis of the third camp was significant: in their attempt to confront the colonizer, the 'traditionalists' took refuge in a 'recovered' pre-colonial past, or more correctly, in a fabricated past, never questioning which or whose past was being recovered. This invariably led to eulogizing 'a pre-capitalist social order ... rather than the grim realities of a people striving under sub-human conditions.' This also leads to the recovery of a specific past at the cost of excluding others.

In their attempt to confront the colonizer, the 'traditionalists' took refuge in a 'recovered' pre-colonial past, or more correctly, in a fabricated past, never questioning which or whose past was being recovered. This invariably led to eulogizing 'a pre-capitalist social order ... rather than the grim realities of a people striving under sub-human conditions.' This also leads to the recovery of a specific past at the cost of excluding others.

The most important figure in this debate is Rabindranath Tagore. Although, he appears like his nephew Abanindranath disengaged from social realities, actually comes close to the idea of Havell and others of the spiritual artistic persona, he is sharply critical of the 'narrow-mindedness' of 'Indian' art. 'I strongly urge our artists', Rabindranath wrote, 'to deny their obligation carefully to produce something that can be labelled as Indian Art by conforming to some old world mannerisms. Let them proudly refuse to be herded into a pen like branded beasts that are treated as cattle and not as cows.' Further, he said, 'when we speak of Indian Art it indicates some truth based upon the Indian tradition and temperament. At the same time we must know that there is no such thing as absolute caste restriction in human cultures; they even have the power to combine and produce new variations, and such combinations have been going on for ages, proving the truth of the deep unity of human psychology.' A 'world dialogue' is seen as fundamental to a modern existence.

Although these two strands - commitment to the idea of a nation, and to the realm of architecture - are tied up in Muzharul Islam's thinking, his architecture remained consciously distant from nationalistic polemics. He understood that nationalistic posturing does not automatically lead to a 'regional' architecture. Here, political ideology and architectural fabrication entered an impasse. But even if unresolved, architecture and politics lie inextricably intertwined. The intertwining raises questions about understanding the premise of architectural production, about the subtle thread of creation and vested interests, and about the nature of social engagement of architecture.

The whole thing brings to focus, on one hand, the figure of the truly artistic persona, as Rabindranath and the architect Louis Kahn, who are suspicious of political arguments, and, on the other hand, the impossibility of political aloofness particularly in nations like Bangladesh and India. Political engagement however convinced Muzharul Islam about the insufficiency of architectural form to address social conditions, and that has gradually shifted him towards a more politicized role.

Architectural paradigms

Humayun Kabir, in his 1944 essay 'Our Heritage,' notes that 'in all modern manifestations of Indian art, the one form which is absent is architecture.' If literature, painting, and somewhat later, film, were thematically confronting the existential question of 'what it means to be a Bengali in the twentieth century,' architecture remained far behind as a mere construction activity. An architectural discourse was clearly missing from the Renaissance movement, despite the intellectual strides of its early period, and the stimulating debates on aesthetics. Even Rabindranath, who had reflected on almost all spheres of human existence, and who had actually experimented with some houses at Santiniketan, had little to say directly about it. Humayun Kabir, pointing to colonialism, insists that the ensuing fragmentation of social collectivity was responsible for a deficiency in architecture culture. It was the individualist art - painting, poetry and literature - which flourished even within the 'ruputurous' condition of colonialism.

The leadership of the building activity was taken up by engineers, earlier by the corps of British army engineers, and inherited later by the new cadre of civilianized personnel, the 'civil' engineers. Even after independence from colonial rule in 1947, architecture remained within the hegemony of the 'civil' engineering profession. The building activity was reduced to a mundane functional manipulation of the box, far removed from an investigation of the spatial, experiential or symbolic dimensions. The principles and typologies of the Bengali building tradition also remained uninvestigated.

It was in 1953, in this imbalanced condition of cultural energy and architectural amnesia that Muzharul Islam began his career. For a thirty-year old working single-handedly, the task was immense: his architectural production involved, at one level, a resistance to the entrenched practice of the engineers, and, at another level, the formulation of a Bengali building paradigm. From the very first projects, the formulation of a paradigm is addressed through a two-fold concern: the question of the house, and the question of the city.

The paradigm of the modern house in the sub-continent is constituted by a chain of developments that originate in the colonial bungalow. The bungalow itself is derived from the bangla hut of rural Bengal (and hence bungalow), adopted by the English as a model of dwelling in the pavilion, from where 'one could see the sunset and the horizon,' and no doubt, from where one could keep a watchful eye on the natives too. It was the latter reason and an imperial imperative that led to the classicizing of the bungalow. The Bengali elites continued the classicized bungalow, caricaturing its details or applying an ornate decoration. The ultimate twist to the bungalow came from modern architecture, and the 'scientism' of tropical architecture, filtering the stigma of colonial architecture to produce the modern model of dwelling. Principles of tropical architecture gave a climatic rationale to the bungalow in the hot-humid zone, while architectural modernism introduced an abstract asymmetrical disposition, jettisonning the classical-colonial imagery and breaking the cuboid geometry of the bungalow into a lyrical composition of planes. Architecturally, the pavilion model was seen as a machine for living in the hot-humid zone, as pictured in certain pata paintings. Sociologically, the modern house responded to the emerging aspirations of an altogether new urban group: the middle class.

Throughout the 1950s and most part of 1960s, Muzharul Islam experimented with a number of house types and techniques: the courtyard house for OR Jaigirder, the vaulted residence for the Executive Engineer of the government, the house-on-stilts, and the parasol house for himself at Dhanmondi. And, there were also many experiments with various techniques: the vault, the brick-and-concrete composite wall, and brick construction. But, fundamentally the early houses, in articulating the paradigm of the modern bungalow, incorporated the spatial and the planar dimension of the classic houses of early modernism. In that period, Muzharul Islam also developed his crafting of architecture, which became vivid in such signature details as the somewhat Wrigtian proportion of windows, in the columns, the openings, and always, in the spatial character of the entrance porch.

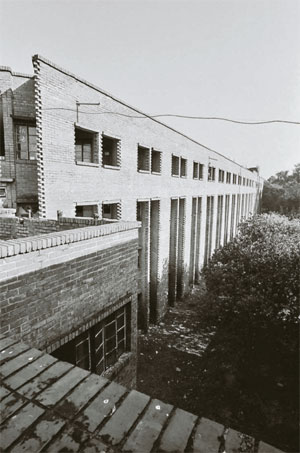

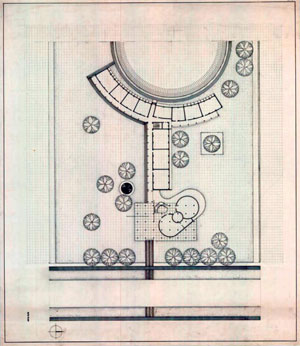

The idea of the pavilion was also behind large projects, from the Public Library and the Science Laboratory to the NIPA building at Dhaka University. The Public Library (1953) was organized in a clearly Corbusian mode - a cubic volume on stilts, complete with ramps, sun-breakers and pristine white colours - but it indicated for Dhaka then a fresh approach to urbanism. The western wing, with its climate control devices of shell roofs and brick louvers for openings, was an original articulation. The NIPA building (1967) signified the pavilion with its array of concrete piers girding the building, with the usable space recessed further behind. The hovering plane of the roof as a chattri (parasol) completed the imagery. The Art College, designed at the same time as the Public Library, stands apart from this group. It came much closer to mediating with the conditions of the place in a sensorial and evocative manner. Sprawling, low building volumes unlike the monolithic Public Library, the use of exposed fire brick which always has such a magical resonance with the 'greenness' of Bengal, the natural garden setting on an urban site, all went to form the atmosphere of a campus that was ideal for the contemplation and learning of the arts, and more importantly, to indicate a spatial environment which evoked the architectural poetics of the land.

Despite the discontinuities which have affected his practice, the works of Muzharul Islam reveal a progression from a reference to the language of certain western masters towards a more personal formulation. The 1960s remain his most prolific period of building. He was also involved at this time in the development of the institute of the architects, and was influential in the drafting of its constitution, for which architects in Pakistan still remember him. Besides his own contribution to the architecture culture, he was also instrumental in bringing Louis Kahn, Paul Rudolph and Stanley Tigerman to Bangladesh. The involvement of the American trio was seen by Muzharul Islam as a necessary occasion for providing visual and provocative examples in the vacuous contemporary situation.

His early projects from the 1950s upto works like NIPA and his own house in the late 60s owe much to Frank Lloyd Wright, Le Corbusier and Paul Rudolph. This is evident, in varying degrees, in the basic skeletal configuration of the works, in the innovation of climate control (the umbrella roof of his own house recalling Shodhan Villa); in the sculptural animation made by varying reliefs, deep shadows and juxtaposition of materials; in the spatial composition (as in the multi-levelled organization of his own house); and, finally, in the manner the buildings confront the landscape with an assertive and self-referential stance (again, with the exception of Arts College).

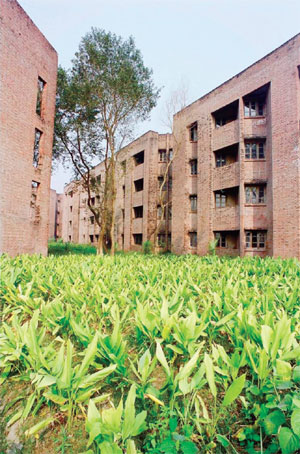

In the late 60s, with the commission of two university projects, involving large-scale organization, began his later phase. The presence of Louis Kahn in Dhaka, ensuing into a dialogue with Muzharul Islam, is more than incidental for this shift. While the pervading order, as in Jahangirnagar University and the housing for Jaipurhat Limestone Factory, is an a priori geometry, the concern is to generate an 'urbanised' order by the formation of communal spatial enclosures, streets and continuous facades, qualities which are not explicit in earlier projects. The individual buildings are clearly of masonry, where spaces and voids seem to be carved out of masonry solids which, despite their often curious geometrical purity and unlike the skeletal nature of his earlier projects, form a more earth-hugging ambience.

The shift is most explicit in the National Library project (1978). It is here that 'distortion' of the idealized form itself became the generator of architecture; the final form acknowledged more explicitly the contradictory conditions of the place and the programme. Gone was the stark clarity of his earlier skeletal work, to be replaced by a ponderous massive presence accentuated both by the centralized form and the use of brick. The building presents a convincing response to the neighbouring ensemble by Kahn, which has by now formed an important context in the north of Dhaka. While geometric abstraction and a consummate skill for crafting constitute a continuity in all his work, the iconography of National Library is a world removed from the Public Library of 1955. The Library is a surreptitious triumph, almost against Muzharul Islam's own rational rigour, of the empirical over the rational, of the accidental over the planned, of the a posteriori over the a priori. Moreover, what has been a materialist constant in his work, that is, the privileging of reason which has lead to a suspicion of mystery and the 'unconscious,' is somewhat undermined. One can with the Library project talk of the reification of the mysterious, and of such anti-Marxist stuff as 'wonder and amazement.'

Vastukala: an existential art

Architect, teacher, mentor, activist, provocateur ... Muzharul Islam remained an institution by himself. Life at Vastukalabid, his office-abode, was always a setting for new actions and movements for a number of generations.

Yet, institutional architecture kept him at a distance in order to marginalize his impact. From the vantage point of current architecture culture, Muzharul Islam always seems an annoyance in the placid comfort of a non-ideological existence. His ethical exhortation sounded shrill in the ears of architectural opportunism.

Muzharul Islam remains a 'tragic' artist, the quintessential modern figure who is no longer a tool, a manifestation of the collectivity (as in traditional conditions). The artist is more of a reformer. More than being a mouthpiece, he remained a social critic. More than being a representation, he re-presented. Every piece he produced, every thought he thought, was not merely a reflection on society but locating what, in his mind, was lacking in it, what was usurpable in it. It was that largely self-appointed role – the usurper of the social strongholds – that inevitably resulted in a kind of futility, lending tragicality to the modern artist. What, however, counted for the determined artist was not the fruits borne, but the seeds sown.

Even if taking on an idealized condition, Muzharul Islam remained concerned with the wholeness of life, the whole horizon of existence. It is poignant that he named his office Vastukalabid, recalling the ancient practice of vastushilpa, literally the art of 'existing'or being, with the root-word vas connected to astitwa, the German wesen, essence, the English was. This is sufficiently distinctive from the idea of the craft of making implied in the Latin sense of architecture (archi, chief; tecton, making). Vastu is not an aesthetical category, but an existential one if by that we can mean the way we situate ourselves in the world, the way we are in the world. This is not something given to us, or we find ourselves in, but is a conscious effort towards construction. Muzharul Islam remained to his last day dedicated to the project of an existential re-construction.

Notes

1) Interview in Sthapatya O Nirman, January-March, 1992.

2) Introduction in this publication by Stanley Tigerman. Also, in What Will Be Has Always Been: The Words of Louis I. Kahn, edited by Richard Saul Wurman, Rizzoli Press, 1986. Also, Tigerman in interview with K. Ashraf in Chicago, 1993.

3) A number of recent studies treat this important period in Bengali culture: Tapati Guha-Thakurta, The Making of a New 'Indian' Art: Artists, Aesthetics and Nationalism in Bengal, c 1850-1920, Cambridge University Press, 1992, and Ratnabali Chatterjee, From the Karkhana to the Studio, Books and Books, 1990.

A shorter version of this paper appeared in The India International Centre Quarterly, New Delhi, 1996, which was reprinted in BRAC book, Muzharul Islam Architect, 2011. The current version was rescripted in 2013.

KAZI KHALEED ASHRAF is an architect, urbanist and architectural critic. His publications include An Architecture of Independence: The Making of Modern South Asia (1997), Louis Kahn's Capital Complex in Bangladesh (2002), the Architectural Design special issue “Made in India” that received the Pierre Vago Journalism Award from the Committee of International Critics (2007), and Designing Dhaka: A Manifesto for a Better City (2012). His recent book The Hermit's Hut: Architecture and Asceticism in India was published by the University of Hawaii Press in Fall 2013. Following a Masters from MIT and a PhD from the University of Pennsylvania, Ashraf now teaches architectural history and theory, and design studios at the University of Hawaii at Manoa.