Features

Unravelling history at the Colombo Art Biennale

TV Santosh's Effigies of Turbulent Yesterdays (2011-2013) is perhaps the most immediately striking, consumable and predictable piece at the Colombo Art Biennale (CAB) that ran from January 30 to February 9, dispersed across seven venues in Colombo, Sri Lanka's capital city. Working around the theme of Making History, or rather 'Re-Making' it (as some of the signage let on), CAB's third edition brought forth an exciting mosaic of international works from across the globe alongside a strong local presence. Effigies was the centre piece at Park Street Mews, a renovated warehouse in a fashionable alley, and overwhelmed it somewhat. Questioning the ideology behind state sponsored monuments and the discourse of masculine power and violence that such monuments perpetuate, a headless hero spurts blood from the neck astride a strapping horse – its metonymic resonances verging on the banal, the piece works thanks to the LED timers spread across the horse's body, rump to nose. Resisting the urge to correspond the timings to specific time zones, Santosh has kept the timings random, which introduces an irreducible element to an otherwise smoothly decipherable comment on the relation between state power, propaganda and the subject.

Chock-a-bloc with works that turn on the individual's right to subjectivity, and more often its lack thereof, the pressing discourse seemed to orbit around migrant labour. Be it Rakhi Peswani's installation involving giant calico bags hung in rows and stuffed with cotton and synthetic wool – unevenly stained in shades of coffee reminiscent of sweat, Inside the Melancholic Object (an elegy for a migrant worker) is geared towards pushing the viewer into emotional empathy with the long suffering bonded labourers toiling away at the many tea/coffee plantations of colonial Sri Lanka. The piece runs the risk of slipping into sentimentality, which is not particularly mitigated by its recognizable indebtedness to Ernesto Neto's works seen the world over. In contrast, stood out the nine stark photo-portraits taken from Qatar's nearly a million strong migrant labour population. Khalifa Al Obaidly documents and conserves history in his homeland and Tagged (2009) is poignant in its objectification of the individual through ISBN codes painted on their otherwise contented faces. In Nepal's Sunil Sigdel's Spine (2014), the individual disappears completely and is replaced by hundreds of workers' gloves sourced from migrant workers. Like a massive garland strung together for a victorious leader, the installation is a chilling visual metaphor for the immense contribution of migrant workers the world over towards the economies of many a developed nation today – often it is they who form the material backbone of a country – and upholds the curatorial philosophy that 'futures cannot be imagined without the people who inhabit it.'

Absolute, masculinist, state power as the defining discourse of South Asian colonial history is central to both Sri Lankan Pala Pothupithiye's and Bangladesh's Mahbubur Rahman's works. Pothupithiye was exhibiting an entire series at the central venue, the JDA Perera Gallery. His paintings were mixed media reworkings of official maps of Sri Lanka and South Asia and were probably the biennale's only paintings on show (except for a floor-piece). However, it is his 257 cm high History Maker (2014) that draws you in – the robed, male figure modelled along classical lines wears a perfectly knotted tie and holds an official looking document rolled up in his hands. Sculpted from metal sheets, the piece yields unnerving details at closer inspection that immediately punctures the discourse seems to it embody at first glance. ‘I wanted to show the violent, dominant masculinist ideology of our colonial past with the knife-encrusted face that has had a spill over effect even on our postcolonial history – the knives symbolize the violence and their refusal to see another's perspective,’ shared Pothupithiye. Bending low, I discovered that from between the figure's imperial thighs peeked a dimly lit map of Sri Lanka with words of the national anthem inscribed on it in Sinhala. Colonial history and its continuing, disabling legacy in South Asia is explored further by Mahbubur Rahman in his sculptural installation Replacement (2014). An unsettling presence, the piece has life-size bridesmaids crafted out of combat leather boots wearing elegant gowns fashioned out of army fatigues standing around in postures of complete, feminine subservience to the central figures – two royal uniforms on stilts. The gowns are embroidered exquisitely with blown up symbols of British colonial rule and two crowns adorn the two figures on stilts – effigies of King George V and his Queen on their visit to the Delhi Durbar in 2011 – as glistening red tentacles stick out like omnipresent claws from underneath. Like Santosh, Rahman explored the politics of image making through a double entendre – in his Replacement, an effeminate, domesticated military colludes with state heads to possibly ‘replace’ democracy even as an Euro-America-centric cultural hegemony ‘replaces’, again, direct colonial rule. In contrast, sat Manori Jayasinghe's simultaneously alluring/threatening King (2014) – a delicate crown crafted from hundreds of pins, acts as a material metaphor for the inescapable vicissitudes of absolute power.

wooden board, acrylic, oil and wax and sealant, archival paper, aluminum light fitting floor: 366x244cm, table: 81x97x74cm, document: 21 pages, 2014.

The curators Amit Kumar Jain, Chandragupta Thenuwara and Neil Butler attempted an exploration of the ‘tension between intimate private histories and the larger discourses of war, territory, nation building … and imperialisms’ with CAB. Concepts of retrieval, preservation and manufacturing of memory are of course vital to such a project. Two cabinets – one displayed on the ground floor of the main venue and the other on its second floor – encapsulate the distinct approaches with which the reality of thirty years of Sri Lankan civil war alongside wider, global concerns have been negotiated at the biennale. Mahen Walter Perera's Memory Brailles (2014) gives the popular 'cabinet of curiosities' format a twist. Pieces of old clothing from Perera's personal wardrobe were moulded with plaster in immediate response to their material presence as well embedded memories by the artist. Almost archaeological in treatment for he 'intimately explores and celebrates the residual', the cabinet and its curious, shapeless objects ossified at unforeseen moments of 'becoming' turn into an allegory for every individual's practice of making and retrieving personal histories. Upstairs, Jagath Weerasinghe's cabinet bearing folded old clothes, books (including Joyce's 'Dubliners' and Sinhala titles), toy chimps, indigenous bric-a-bracs and wax blocks bearing shaving paraphernalia, coke cans, shoeshine etc in a cryogenic freeze is minutely detailed in its objective documentation of subjective history. Aptly called Bad Archaeology (2014), Weerasinghe, who is a renowned archaeologist himself, hopefully points towards the pitfalls of any project that hopes to derive from official narratives.

An idea further explored by Scotland's Jo Hodges and Robbie Coleman's interactive one-off performance Witness: Remember: Forget, where the duo invited random viewers through a mock-official scenario of first looking at and then recording personal impressions of a set of photographs under tight official guidance/scrutiny. Kafkaesque in its resounding absurdity, the piece's only official documentation is the thoroughly intimidated viewer/participant's response through written texts. The texts are later displayed and subsequently given away to street vendors for use. Dismantling the entire process of official history-making, the piece successfully tears apart the magic fabric of glorified, personal memory. But Sri Lankan Koralegedara Pushpakumara's Illuminated Barbwire (2014) flickered in beautiful contrast with strings of mini-bulbs going rhythmically off-and-on inside lengths of transparent tubing that resembled barbed wire – subtly questioning his nation's efforts to gloss over the wounds of civil war. Ringing a bell with anyone familiar with the South Asian tradition of festival pandals, the piece immediately pulls in associations of suffering and violence against a backdrop of intermittent festival respites and unrelenting political unaccountability.

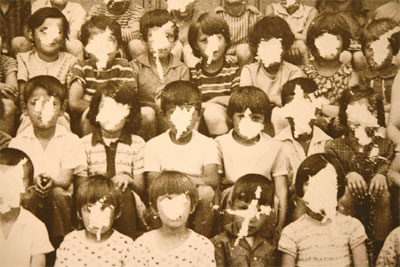

Armed with the diverse arsenal of intensely personalized memory, extensively researched documentation of found materials and sometimes even fake histories, the artists at CAB have tackled the projects of violence, war and history. Irish Anthony Haughey's monumental presentation was a composite – Disputed Territory (2006), Class of '73 (2006) and the H Block Archive (2014), together brought photographs, videos and texts in an attempt to recover lost histories – be it of refugees who poured out of Yugoslavia to Macedonia in 1999, of Albanian children destroyed by ethnic cleansing projects, or of the Irish resistance of 1990s. On display were 360 passport-sized photographs of individuals taken by a high street photographer in Macedonia. The man's 27,000-strong archive has already 'disappeared' while Haughey had been able to track only 360 – of ordinary people desperately fleeing Yugoslavia. A c-print of a badly scratched 'class photograph' stares back at you from one wall – 39 students and their teacher in a school in Kosovo, each and every one of whose faces have been scratched out – probably by soldiers bent on brutalizing if not totally annihilating the other's history. Of the 39, 22 cannot be even identified or traced. Haughey's Class of '73 has become a 'performative cultural artefact' that tries to channelize memories of the forgotten into the current local Albanian population as well as within wider contexts. More importantly, it reaffirms the artist's responsibility as an archiver of alternative histories. A point that Jesper Nordahl of Sweden makes with Documentation of a Public Monument by Minnesministeriet (2013), an unofficial monument in the form of a plaque 'commemorating' police firing at demonstrators at Gothenberg in 2001. Here, raising the monument invigorates an ideology of resistance as opposed to Santosh's, or even Pothupithiye's earlier interpretations. Interestingly, Jake Oorloff of Sri Lanka adds a further dimension to this dialogue with his performance that presented official speeches as the monuments of ongoing history-making projects the world over.

Three CAD drawings stood out in their imaginative audacity at the Post Graduate Institute of Archaeology. Called Kettling (2011), Gihan Karunaratne's pieces map out the best possible ways to corral protestors around St. Paul's Cathedral, Trafalgar Square and Bank of England with clinical efficiency. Eerily, the project materialized only after the artist had extensive discussions with senior police officials in London and therefore, can be taken as an instance of how an artist's function can be contained and used against society. Karunanratne's other pieces mitigate this – giclee prints of Google GPS digital trackings of his own iPhone pose resistance to the insidious surveillance being carried out by tech giants on unsuspecting consumers.

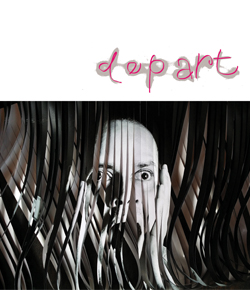

Silent resistance is the charge behind Pradeep Chandrasiri's installation Things I Told, Things Not Heard and Things I Tell Now (2014) that explores the inevitability of compromise and the manipulative role of 'power' in every political dialogue. The physical remnants of a scar tarnishes the close-up of a scrubby head in a massive photographic print acting as a backdrop to two ornate chairs facing across a table – all drowning slowly in a quagmire of black, burnt charcoal. Says it all!

sculpture with metal, rubber, plastic, 162.5x 66x152cm, 2014.

Memory, especially as a record of women's personal experiences in a dominantly masculinist world, occupied considerable space at CAB 14. On a more generic note appears Anoli Perera's Memory Keeper: Red Cupboard (2014), in which Perera projected a video loop of women's hands – performing everyday, genteel feminine tasks like serving food on delicate chinaware, cleaning silver trays or putting away cups in a cupboard – behind a screen made from typical Sri Lankan lacework. Underneath, china cups spill out alongside fabric balls in a tumultuous wave – in an exciting attempt to transpose remembrance into the material, tangible realm of 'things'. In the Herstories Project (2014) curated by Radhika Hetiarachhi, the mother's memory culled from oral narrations, letters, tree-of-life maps and charts record the traumas experienced by ten different women during the civil war. The texts therefore, peek into the lives of entire communities through single memory strands. Part of a much larger 'Herstory Archives' project, the archival artwork has evolved into an instance of how personal, subjective, feminine memory, which is usually suppressed and channelled as the alternative, can and should play a vital role in the making of a nation's official – a theme explored by Sachini Perera and Natalie Soysa in I Was. I Am.(2013) as well. Fabric of Time (2014) is the end result of another participatory piece mobilized by the Fireflies collective and brings into the gallery a quilt of sorts – of sarees, old clothes, jewellery, threads brought to the project sites by women across Sri Lanka and who have themselves stitched the material together to create a lived history of their times.

Thor Mc-Intyre Burnie's I Can Feel the Pain in that Mother's Heart. And I Am Glad That I Can Feel It (2014) is a sculptural installation which also mines similar emotional charges. A helmet cut out of a wok – an utensil of inevitable daily use in Sri Lankan kitchens – hangs by a thread over a heavy brick which seems to have just fallen out of the wok/helmet and landed on a small mound of sand underneath. Outstanding in metonymic dexterity, the piece slips smoothly between multiple registers – as does Janananda Laksiri's video Tight Rope Walk (2012) which is a remarkable take on 'la condition humaine' and succeeds brilliantly as a 3.44 minutes recording of the artist trying to walk across a mesh of electric wires midair.

The idea of the alternative arrives at 'multiplicity' of perspectives, and therefore, contiguous histories in Layla Gonaduwa's The Silverfish (2014) in which she reconfigures a chapter of the ancient, epic Sinhala poem 'Mahavamsa'. Rearranging the letters on each page through ten possible permutations,

Gonaduwa arrives at multiple narratives, each completely different from the other! And the marks left by silverfish act as metaphors for the absences and silences that every narrative must allow within itself to emerge coherent. Gonaduwa has played around brilliantly with the idea of 'Making History' in a very literal sense. Poornima Jayasinghe's Towards a Bright Future (2014) is a multi-media installation that highlights the same kind of silences and manipulated absences – taking over a women's toilet at Park Street Mews, she converted it into a healing station for men and women, who are lured by the state with the mirage of a bright future that glosses over Sri Lanka's recent past. Participants are invited to use footmark imprinted toilet rolls, reminiscent of personal experiences they are advised to discard, and spray air fresheners to a lilting English background score of farts and flushing water interspersed with directions to relax and breathe and forget everything. Pertinent indeed!

Live art as well as conversations with artists, art writers and scholars were an important part of CAB 14 with the section being curated by Ruhanie Perera. Sri Lankan and international performance artists took over the streets and galleries of Colombo – be it Eugene Draw playing the violin in response to Tristan Al-Haddad's site specific Womb/Tomb or Eva Priyanka Wegener and Thomas Pritchard prancing across the gallery spaces to embody the spirit of every artwork. On a more political note, veteran Sri Lankan performance artist Bandu Manamperi disrobed on public streets to iron out the creases in his clothes as an act of resistance to official history's obsession with a creaseless, happy narrative. Kumari Kumaragamage's multiple performances explored the same theme from the position of women who have suffered personal loss during the war. Hannah Brackston's The Brushes of Wewalgoda (2014) was the result of a residency in Higgaduwa organized at the Suramadura Centre by Neil Butler's UZ Arts. She exchanged household brushes in the local community for new ones. The resultant artwork looks like a performance in stasis, so loaded are the objects with domestic memories, that they ostensibly stand as monuments to the 'personal'. In an impromptu performance by the great physical comedian Adrian Schvarschtein, brooms take centre-stage , as tools to arm oneself with in response to artworks at the Park Street Mews!

Chintaka Thenuwara's cyclical installations were present at every venue, perhaps, as reminders of the curators' thematic engagement with time? And perhaps, as a cue to the inevitability of change, too. Patterns of Distortion (2014), Gray Scale (2014) and Acts, Results and Consequences (2014) sets into motion modified bicycles to record, playfully confront and negotiate the ideas of uni-linear reality, its fragmentation and subsequent overreaching effects.

One of the most poignant pieces in the biennale is a video – a four-minute HD video loop by Sri Lankan Danushka Marasinghe. Concealing Marks (2012) runs as a close-up of army boots attached to masculine ankles walking across a stretch of sand segued to a rhythmic, painstaking process with which every footprint is wiped out by an indigenous broom. Meditative, minimal and piercingly effective in its perfect correspondence to every nation's state manufactured history, the work resonates across cultures in its open-ended embracing of possibilities, interpretations and an innate element of resistance. In itself it can act as a metaphor for the entire biennale – whose success and relevance was supplemented by the Homelands project brought by British Council (curated by Lathika Gupta) and the Rosemary Trockel retro supported by Goethe Institute that tries to question the paradigm categorizing the 'woman artist' even to this day.

KURCHI DASGUPTA is an Indian artist and writer based in Kathmandu who works in the capacity of a freelancer contributing art writings to both regional and overseas magazines.