obituary

A Sudden Departure

Looking back at life and art with Qayyum Chowdhury

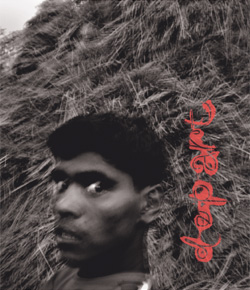

Qayyum Chowdhury, country's most celebrated artist, died at the age 82 on November 30, 2014, after collapsing on the stage during a music festival. His decisive contribution to the pre- and post-independence cultural firmament made him a household name. The cultural figure that he became was linked with his organic engagement with two divergent fields of practice – graphic design and painting. And in both arenas, his easily recognizable motifs and imagery, inclined to evoke the rural, help to conserve his reputation over the last four or so decades. As he was particularly interested in some crucial aesthetic stratagem of employing the forms and lines to forward a deshi brio of his own making, his paintings were often considered as an extension of his graphic sensibility. For his contribution in art, he received Ekushey Padak (title) in 1986 and Swadhinata Puroshkar (independence award) in 2014. Following is an excerpt of a conversation with the artist taken a while ago, October 1999, to be precise, by artist and researcher SHAWON AKAND.

Photo courtesy: The Daily Star

Shawon Akand: You are associated with the arts for almost fifty years, filling in different roles at different times – the roles of student, art-apprentice, designer and teacher of the Art Institute; but over and above everything else, you are an artist. I would like to know how your thoughts and feelings of the time when you first got engaged in this field differ from the way you feel about it now.

Qayyum Chowdhury: When we first joined the Art school as students, our goal was mastering the skill. It was in 1949 when I enrolled there with the sole aim of learning the art of painting. We never considered job prospects on completion of the course. There were hardly any professional fields open for artists in those days other than the job of a drawing master and still we came to the art school to fulfill our passion for art through learning the craft. Nothing else mattered to us. We never thought about anything else because we were wrapped up too much in our boundless enthusiasm and craving for art to give time to any other thoughts. The idea was like facing situations and working out solutions as they come.

SA: What did you do after this?

QC: When that phase was over and we came out of the Art Institute, the situation was the same – the dearth of job opportunities. In spite of that, I managed my expenses through various types of employment in different publishing establishments, advertisement agencies, newspapers and magazines. I passed in the year 1954 and got my first job in the Art College in 1957. In 1960, a design center was established under BISIC with Quamrul Hassan as the chief designer. Quamrul bhai wanted me there and I left my job to join him, though I did not continue with the design center for long. It was just one year and then again I returned to work for news magazines, ad agencies and publishers. Then once again, in 1965, I got employment in Art College. Whatever way we might have passed our time, I feel, even after these fifty years, that it has been a perennial learning process, unrelated to time or age and our art education is still going on and will continue through a life of learning and creating art.

SA: After a long break, only recently there has been a solo exhibition of your paintings at Shilpangan. Why is this long gap?

QC: There is a reason behind this delay. As I have said earlier, I passed from art school in 1954, but didn't get a job right away. I felt the urgency to earn; how long can one depend on one's father's coffer, expecting the family patriarch to provide sustenance? So between my job hunting and making a living through commercial painting, there would hardly be enough time left to indulge in my artistic pursuits. So I could never gather enough painting for a solo exhibition. In those days I could only participate in group exhibitions and national art shows for lack of adequate artwork of my own to present as a single exhibition. A permanent employment had been the missing factor for the mind to tune in for total dedication.

SA: But didn't you get the employment in as early as 1957?

QC: Yes, I did continue painting when I got the permanent job, but as I said, could not collect enough work to present as one exhibit, which accounts for the long interval. Later, in the year 1977, when I observed a substantial amount of work had accumulated, my first solo exhibition was held in Dhaka. Before this I used to illustrate book covers for which, in 1975, I was awarded gold medal by the Jatiyo Grantha Kendro for my contribution in publication. On the occasion of the award giving, the Jatiyo Grantha Kendro held a book cover exhibition where about 300 to 350 of my covers were on display, but there was no painting. So my first exhibition was in 1977, the year when I went to America and held my second exhibition there, and the one taking place now (1999) is my third show.

SA: That means, this one is happening after almost twenty three years.

QC: It is a sort of coincidence. Before the exhibition, one day Belal Chowdhury came to my house to see my paintings. He said, 'You are holding your third solo in 1999; when exactly did you graduate?' I said it was in 1954. And when was your first show? It was in 1977. The calculation showed that after twenty three years of passing from the art school I had my first show and then, at the wake of the next twenty third year, I was holding my second one. So, his suggestion was for me to put forward one hundred and twenty three works, synchronizing with the other twenty threes and that is the number of paintings being displayed in this exhibition.

SA: An extensive use of folk motifs is quite noticeable in your work, which possibly accounts for you being considered by many as a successor of Jamini Roy or Quamrul Hassan. What is your personal response to that?

QC: But I don't feel my work can really be approximated to folk motif in the real sense of the term.

SA: Still, one cannot overlook the indigenous influence in your work, for example, the color…

QC: Oh yes, there is a popular influence. You may call it a kind of transformation where I have adapted the folk motifs to suit my personal taste. For example, the fancy pots, Lakshmi's earthen lids, wooden elephants, horses and dolls – all of these are there. I perceived color as the most important aspect of my art and used it in its exactitude. My earlier works do not show this conscious choice of color – it was almost like I was fumbling for the right direction.

SA: There is rather a Cubist influence noticeable in your earlier works.

QC: That was a mix up. There was something about Zainul Abedin's teaching. In painting we were trained under the British system. But he always emphasized on our keeping in mind the legacy of this subcontinent. He never imposed his ideas on us, never insisted on us working on a particular subject. He would simply guide our visions towards it. Let me recall an incident from that time. Our house in Naya Paltan was just behind Zainul Abedin's residence. I was the chief artist of the Observer Group of Publications. In those days, Sundays used be a holiday. After the week long work, on Sunday mornings I used to go to Mr. Abedin's house. There was a nice porch in front of his house, where he would spend the mornings smoking cigarettes and conversing with people over cups of tea. I also used to fraternize with them. One day he asked me, 'I see some illustrations on the Sunday Magazines of The Observer. Whose are those? One particular image is of a strange shaped boat with an interesting drawing on the prow, the centralized eye of that drawing suggests a gaze. Is that your work?' I affirmed, adding the fact that with the work load at the office, I had very little time for pursuing my painting.

SA: Did this incident stimulate you in any way?

QC: Of course. There was this distinctive feature of Mr. Abedin, that he could inspire people amazingly. I was intrigued by this – a person like him even noticing my illustration. He told me, 'Think of this boat, anchored in the river bank… two of them… may be many, with their many eyes, just gazing… can't you think of such a composition in your painting?' I was dazed! It was so true and yet it had never crossed my mind.

SA: You have a complete series on the theme of boat.

QC: Yes. And then, after a couple of days he suddenly said – well, I have noticed something – your bedroom light is on in the evening, then at ten it is still on, so it is at twelve and at four in the morning. What do you do through the night?

I said, Sir, it is a routine developed to accommodate my newspaper job. My office hours are from nine to five or six in the evening. On my way back I do my groceries from Ray Shaheber Bazar and hand it over to my wife. Then I have some afternoon snacks and take a nap. In the meantime, my wife does some cooking and wakes me up at ten for my supper. Then I sit at my canvas and stay absorbed in my work till morning when it is about time to return to office. Abedin sir kept quiet for a while and then said, 'One day you'll get the result of this.’

SA: What happened then?

QC: I was continuing with this rigmarole when one day – it was a Sunday – at around midnight, my wife and I had just returned to my Naya Paltan residence after visiting my father-in-law's at Azimpur, when there was a knock at the door. It was the younger brother of Zainul Abedin, my friend Janabul Islam. He said boro bhai is calling you. I went. There he was in his lungi, bare torso, with the vest hanging on the shoulder. He beckoned me to go closer. Then suddenly gave me a resounding slap. I was flabbergasted wondering what happened! Then in an instant he drew me in a warm embrace and said, 'This evening I received a telegram from Lahore with the news that you have been awarded the first prize for painting in the National Art Exhibition.' I burst into tears, bawling – sir, it's all because of you! Yes, he had this capacity to inspire and this is how Abedin sir and his teaching worked.

SA: That explains the distinctive guidance and influence of Shilpacharya Zainul Abedin on your work – the way you incorporate the folk elements in your art.

QC: As I said, it's his teaching. He would induce us to observe the crafts, but never asked us to base our art on these observations. Whenever there was a cultural program in the Art College, he would invite the folk singers of this country, Abdul Alim, Kanailal Sheel, Mamtaj Ali Khan, Nina Hamid and the likes to perform and entertain us. There used to be folk instruments like Dotara and Flute - all of these to get us connected with our tradition.

SA: Had there been some other reasons behind this? What I am trying to say is, those being the days of Pakistani rule, was this to instill a nationalist passion or cultural awareness?

QC: That comes later. But first of all he wanted to infuse us with an awareness of our location, background and the conceptualizing of our motherland. By the time we passed from the college, the Language Movement was already over. An effort was going on to impose Pakistani culture on us, not by the use of force, but through creating a political façade like transcribing Bangla in Arabic script, a kind of movement towards imposition of the so-called Islamic culture on us. I remember an event of which I cannot recall the exact year – could be 1964, when an exhibition was put on at Art College. Abedin sir designed the entrance in the form of the layered roof of a hut, decorated it with items like winnowing trays and clay lids, served the guests with artfully designed pithas (rice cakes) brought from Mymensingh and there was also a crafts shop selling ethnic dolls. For some reasons, there occurred some skirmish among the students, some kind of conflict that almost brought the programmme to a point of dissolution. Abedin sir called them and I was there too. He asked, what is this row about? We are trying to serve a purpose, which is to demonstrate to them that it is not easy to impose their culture on us, because ours is not to be neglected – it is rooted to our soil and rich in its content. That gate, the pithas, the crafts – the Pakistani bureaucrats came and saw these, tasted our food, and realized our stance. This is our protest – our statement – never try to invade our culture. That means he showed it through his acts, never uttering a word and it was an eye opener for everyone. Whenever we went on college excursions, to places like Modhupur or Munshigunj, he would invite numerous intellectuals of Dhaka, poets, litterateurs and singers, many of whom would join us in these trips. This was his gesture of establishing a contact between the artists and the intellectuals, maintaining an interactive relationship between them. So, when I was just a student, the poet Jasimuddin was talking to me with his hand on my shoulder – you cannot even imagine this now.

SA: The students of the Art College did have a role in the Language Movement when you were there.

QC: We were planning to hold an exhibition at the old museum in Neemtali, exactly when it happened. Lady Viquarunnesa Noon was to inaugurate the exhibition on 22nd February. When we heard of the shooting, Quamrul Bhai announced that the exhibition would have to be postponed; it would not go on and we all agreed - no way. On hearing everything, Abedin Sir gave his consent and after that, the long procession of 1953, commemorating 21st February started at the Sadarghat Art College and traversing through the city via Islampur and Abdul Ghani Road, ended in front of the Medical College. The students of the Art College including Rashid Chowdhury, Murtaza Basheer, myself and many others led the procession and our students continued being at the forefront of all the cultural and political movements till the independence in 1971. We were the first to hold up a placard saying 'Swadhinata' in our art college procession. I still remember the four placards bearing 'Swa', 'dhi', 'na' and 'ta' being carried by Shameem Shikdar, poet Sufia Kamal's daughter Tulu and two other girls. All of us, even Zainul Abedin sir were in the procession – cannot remember the exact date, it could be 23rd March or a few days before that.

SA: It is also remarkable – the role of the artist community in the Liberation War in terms of its taking a stance and involvement.

QC: The artists have always played a very important role in the war. A revolutionary council of artists, Sangrami Shilpi Parishad was formed, of which I was the President and Murtaja, the Secretary. Until the crackdown of 25th March, we carried out our work from the college hostel. The army assault of 25th March took away the life of Shahnawaz and Mohammad Kibria escaped inevitable death by sheer chance, thanks to an army major amongst the attackers, who happened to have some understanding of art. He was made to stand with the cocked rifle aimed at him when suddenly this officer made his appearance. He looked at the paintings and asked whose work they were. Kibria said he was an artist and those were his work. The officer then asked him about his portrait of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, to which Kibria said he did not have one as he did not draw Sheikh Mujib's portrait. After looking around for a while, the officer left with his troops, advising him to stay behind closed doors, not to open for anyone and not to go out. So fate gave him this second chance in life.

SA: Please let us have some specific ideas about those who were there with you at that time.

QC: Everyone. Everyone was more or less involved. Something that you need to understand is, there were no Rajakars or collaborators among the artists and so it was not possible for them to identify and track down their victims. Let me recount an incident from that time. Following the Army crackdown, on the morning of 26th March, Kibria visited my house at Azimpur, jaded, pale faced. I quickly invited him in and he stayed in my house for a couple of days. It was a time of great anxiety, because all our papers, placards and banners were in our College hostel and if somehow the Pakistanis got their hands on these, then we were done for. And we could do nothing. Then one day, Syed Abdullah Khalid came to my house. I explained the situation to him and he said – nothing to worry sir, I'll look into the matter. Later I heard that he had sneaked into the hostel, wrapped up all the papers, banners etc. inside a mattress and set them on fire. Great courage!

SA: Now, coming back to your own field – you worked simultaneously in two different areas, designing and painting, being successful in both. How do you differentiate between commercial design and art proper?

QC: If you see my graphic work, maybe you will understand that they have some sort of compatibility with my paintings. I have tried to merge the two processes. There was a time when I started my job of cover designing, I had to do it in conformity with the publishers requirements. They would expect me to present a layout first. Maybe they would reject the first attempt, or even the next one before deciding on the final. Sometimes I used to try to bypass their suggestions and opinions and present my own perspective of the work. In this I would be helped by writers and poets, because, after all, we belong to the same class. They used to explain the meaning to the publishers so that a time came when my very first layouts were getting approval without the hassle of multiple attempts. Then I started trying to convey my painting related thoughts and feelings on the covers of the books. I had seen Quamrul bhai also working on the dual field of painting for art and commerce. Sometimes I heard him say that commercial art has a tremendous impact on painting so that your artwork has the possibility of being commercially inclined. That comment had inhibited my consciousness so that I reversed the process, always trying to let my paintings correspond with my cover designs and as I continued in this strategy, the publishers gradually acquiesced with the style. This is how the two fields never came in conflict, the difference between the two being, there is calligraphy in commercial work which is absent in art.

SA: It is your guidance that has modernized the publication industry as well as graphic design in Bangladesh, raising it to a prestigious height. Now, keeping in mind the rapid technological innovations of modern times, introducing computer generated designs, how would you compare that with the kind of manual designing taught in our institutes?

QC: I do believe in the tremendous advantage associated with the ever flourishing field of technology and this can complement our own conceptualization of art. It is a convenient tool for creating impressive visuals with a variety of gimmicks for added interest. One outcome of this is the emergence of eye-catching covers though at the expense of a dimension which still exists in the Bangla across the border. Kolkata was once the capital of undivided Bengal, we used to live there and left only after the formation of Pakistan but still share a common cultural heritage and a common background. Even after the partition, we used to get books from Kolkata and there was an establishment called The Signet Press.

SA: Was it the place where Satyajit Ray used to work?

QC: Yes, Satyajit Ray was associated with the press and one could identify the theme of the books from the covers that he created. Many of those books I bought, being tempted by the covers more than the subject and I have the maximum collection of those books. There was something like perspicuity in those covers. I have never seen such perfection achieved through the use of just one color. The effect of technological advancement is noticeable there in West Bengal too, but I feel there is a dearth of a kind of brilliance and sincerity that is present in Satyajit's covers. Many young people nowadays are designing book covers which are not too bad, in fact some look quite attractive and some are really good. Initially, being carried away by the technological fad, the young designers produced some vapid covers which were nothing but that, an outer layer, devoid of significance. Another problem was the homogeneity of the designs, you could not distinguish between the covers of nonfiction, novel or poems collection, say all of them might depict female visage which didn't make sense. Now things have improved a bit, I would say. With time, the temptation to flaunt ones skill of using a clever contraption is gone.

SA: Let us return to painting. A significant bulk of your work revolves round concepts like childhood memories and a looking back at the rural life that is left behind. It looks like in front of the canvas, confronted with the matter of selecting your theme, you are preeminently caught up in nostalgia.

QC: That is natural. I always believe and maintain that maybe ours were better times, more beautiful; I would not say the present is unpleasant; memory is always radiant with a beauty of its own. Maybe the present generation, twenty years into the future will find this present better than theirs. So very naturally, childhood memories stay rooted in our heart. And speaking of village life, that is the true Bangla, and it was Zainul Abedin who had acquainted me with it. Without his guidance I would never have discovered the true spirit of Bangladesh.

SA: And that is why contemporaneity is a missing factor in your art, resulting in its representation a Bangladesh which is only beautiful and picturesque.

QC: What about my paintings on the Liberation War – do they send the same message of a beautiful Bangladesh?

SA: Well, but still…

QC: This is because painting can hardly be contemporaneous. Tolstoy's highly successful novel, 'War and Peace' is based on a past as far back as about two hundred years. You need to develop a perspective to view your subject in a creative way. A portrayal of current event becomes a poster, not painting.

SA: But Picasso's 'Guernica' has been a depiction of his time.

QC: Where was Picasso when he painted 'Guernica'? He was away from home, charged with a tremendous longing for a home … his place of birth was on the brink of annihilation.

SA: He was in Paris then.

QC: Yes, he was residing in Paris, unable to return home bearing an agony tormenting him from within. Exceptions must occur. Like my 1972 pictures of the genocide are instantaneous responses to my inner torment – the torment of watching my homeland suffer. I do not know if you have seen 'Bangladesh 71'. When we took our artworks to Kolkata, six of my paintings were on the genocide, done within one year of its occurrence.

SA: Then again, we hear such complaints that our nation has fallen short of producing the expected high quality in art or literary work that might have been inspired by the liberation war.

QC: Only time can tell that. Like the revolutionary poster of Quamrul bhai was a spontaneous production and so were Zainul Abedin's drawings of the famine.

SA: From these examples, can't we deduce that an artist is preeminently influenced by his own times?

QC: It depends on the situation. In 1971, poet Shamsur Rahman did write Bandi Shibir Thekey, (From the Prison Camp), and how did he do that?

SA: Those poems were pseudonymously published in the Desh magazine.

QC: Yes, he wrote those, and wrote from this Bangladesh. He had the advantage of being able to hide a poem inside a cigarette packet, which I could not do with my canvas. Only time and experience gives you the momentum. I personally feel it would be wrong to say there are no good paintings from that time, in fact there are some really good ones for documentation.

SA: As one of the best artists of our country, what advice do you have for the younger generation?

QC: For the young artists I visualize a bright future with plenty of scope for development. In our times we were totally out of touch with the outside world, did not even know what was going on in a place as close as Kolkata. Now we are living in a global village, connected with the world through the superhighway of information technology. Through greater opportunities and wider international exposure, we see the emergence of a substantial number of excellent young artists and there are more to come. So there is nothing to worry about.