Features

From within an aesthetic nowhere

Dissecting 19th Young Artists Exhibition

Looking from within the interlocking domains of art and art criticism, the 19th Young Artist Art Exhibition 2014, the official title of the art show of emerging artists of below 35 age bar, seems like an estranged, nondescript archipelago. Mapping such a location in the context of the changing cultural patterns of Bangladesh becomes impossible as no particular body of work seems to clearly lead one to the new drift(s).

When an exhibition collapses into an unstructured arbitrary agglomeration of artworks with entries passed without much value judgment, it effectuates a desertification of the field of vision through which one is supposed to determine one's areas of interest in order to write the 'narrative of the new'. The perception of the 'new' on and around art doesn't come without contending issues and parties rallying around those issues. However, amid the chaotic flood of two- and three-dimensional works that embrace the modernist tradition with their threadbare or frayed

link to the past practices in Bangladesh, which constitute this cultural desert, encounter with art itself collapses into a mad search for imagery that may raise the level of adrenaline among the aesthetic kind.

In the last three or four editions, the venue became a dumping ground for academic staples. Thus, the experience of looking at art over the years has taken a regressive turn due to a peeling away of layers whose presence, had it continued to take into cognition the current developments, might have given this national-level, biannual event a sense of purpose, a character that it always needed to have. Instead, this exhibition space, which serves as a magnet for public attention, is now forwarded in the shape of a vortex, where one risks getting lost.

Even looking for fine pieces that hinge on established aesthetic mores has become a challenge, let alone deciphering a new face or form announcing emerging tendencies. In retrospect, the last 'young art exhibition', as it is unofficially referred to, made the emerging art or art trends, for that matter, appear hard to find and difficult to discern.

If this exhibition is an attempt at constructing a roster of artists currently working in the art scene, then it is a flawed roster, an incomplete one that, in its ceaseless projection of art of the young, fails to differentiate between the 'relevant' and the 'superfluous'. If the relevant is represented by artists such as Afsana Sharmin Jhuma, Shimul Saha, Khokon Chandra Sarkar, Sumona Akhter, Palash Bhattacharjee, Suchayan Paul, Ashim Halder, and even Bishwajit Goswami, the superfluous can be underlined in languages that rest between the youthful zest for displaying an ability to paint and a hunger for socio-historical relevance which often degenerates into representation of the 'real' in the forms of half-baked ideational or narrative frames. Thus, appropriating either trite academic realism or/and a perverted and minced surrealism (that have littered the national-level exhibitions of the last 10 or so years) has become an obsession of the artists from the younger generation.

From a linguistic perspective, to make meaning as well as achieve expressiveness, as art is an expressive medium when it is not embedded in conceptual languages, the linear relationship between form and content seems to have made the art of the young way too 'deterministic' contrary to the open-endedness underlining many a successful artistic idioms. In this era of overproduction, often, personal agendas or propaganda gambits are being forwarded as art. Here we can hark back to a succinct remark by Sanat Kumar Saha, whose quote, used in this changed context, may give a foundation to the process of creativity. In an article written on Rabindranath Tagore's poetry, Saha expresses his obvious preference for the poet's mid-life writings where there was 'a scaling down of the personalized intensity, and growing maturity and complexity of content'. This may be considered an axiom to follow. All one may add is that the 'complexity of form' has an equal share in the making of art.

When we are attempting to judge the merit of a national-level exhibition, voluntary exclusion of the bold and the mutinous, who, in their attempt to distance themselves from the mainstream dross, choose not to submit their entries, is of peripheral relevance. What is at stake is the method of sifting through the entries which are being sent for appraisal, and also the fact that a framework for evaluating the latest production seems yet to come into existence in the form of a guideline for the jury members to follow. As there is no official standard to fall back upon, whoever sits on the jury simply gets to choose and pick as he/she goes through the motion of selection driven by personal taste and priorities. At the end of the day, what is being promoted as art from the new generation gives a false impression of the emerging art scene.

What has become obvious over the years is a bias towards an array of artworks that come close to achieving verisimilitude or an established compositional logic set by geometrically inclined abstraction and even a form of politically-tinged art that is neither critical of the bourgeois academic realism, nor is aware of its linguistic and rhetorical limitations. The struggle to achieve verisimilitude, it seems, must be replaced by the struggle to formulate a 'voice' in the midst of all the chaos and misadventures, which is can be likened to a search for a language of local and global relevance.

All things reconsidered, even if one attempts to appreciate what once used to be considered 'standard' in the academia, one is able to spot only a handful of exemplary artworks. If the academic excellence in figurative composition is represented by Md Tanvir Jalal, in his Idea of Freedom 1, Farzana Ahmed Urmi represents the best in the abstract strain of art through her Lines in Mood series. These works provide a respite from all that are trite and all that seem like a forced regurgitation of what is being now valued by those academics who fear a turning of the tide towards the digital media and other forms of experimental art that blur the borders between disciplines.

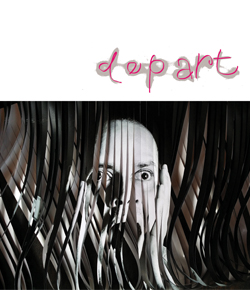

In the current constellation of art from the youths, what seems to keep alive the spirit of transgression is a number of mixed-medium and sculptural pieces, alongside a few installations. Having received recognition for one's experimentation in such a context seems like a blessing in this slowly deteriorating culture of institutional practice of selection and award giving, which, in turn, is one way of giving salience to the 'culture heroes' in the making. Mohammad Mojahidur Rahman Sarker and Khokon Chandra Sarkar seem to have successfully made it by dint of their artistic merit. They respectively received the Best Award in installation (for Autobiography of an Incomplete Man) and an Honourable Mention (for Foster Mother 3).

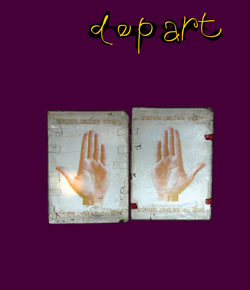

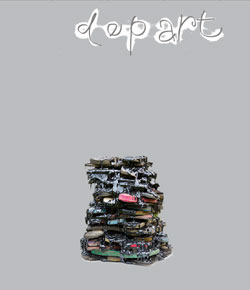

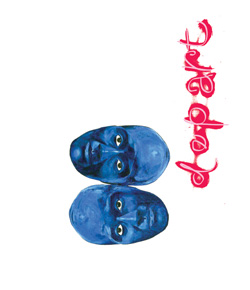

On another plateau rests the most interesting pieces – Shimul Saha's Reason Behind the Activity, Afsana Sharmin Jhuma's Red Line – representing the two antithetical aspects of installation art – the former showing an avid interest in the odhora, or the intangible elements such as light, and the latter addressing the implication of an electronic age with reference to waste matters such as circuit-boards laid out around a video showing a red bandaged figure struggling to keep the body and mind in alignment inside a main switch/ fuse box. The deshi or local art scene has always been a bifurcated one where once abstraction was the polar opposite of the figurative genre. It is necessary to move away from that obvious register of bipolarity to enter into a new form of bipolarity where the 'meditative' is set against the 'interrogative', or the ideational/synaesthetic against the 'transgressive/corporeal' spirit.

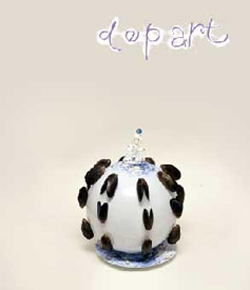

A number of artists are also precariously situated between the two extremes of sensibilities represented by the above–this fact too will have to be registered. Against the Baroque musculature that has fed the imagination of the new generation, who perhaps have begun to take to this genre unwittingly in their desire to match the feat of a number of successful young painters before them, there must be a school of artists working to realize their aesthetic goals. It is these in-between, moderate artists whose works, if represented adequately, may serve as the basis for appreciating some of the variegated interactive strains of art that have emerged since the new millennium. Of middling talent, yet showing a lot of promise, Md Abdul Guffar Babu, with his Dark Moon 1, Munmun Nahar represented by a series of prints entitled Inner Feeling of City Life (Series 1), or Al Amin whose Mother's Love, a sculptural piece, bears testimony to the experiments the academy once promoted.

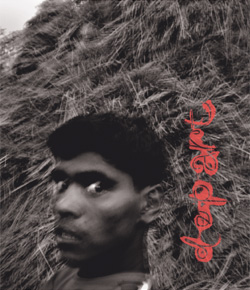

Dhaka art scene never managed to frame the narrative of the new through the processes of qualitative judgment, but there had always been a sieve through which to recognize the talents, if not the drift towards the 'new'. And the standard enforced was often reached intuitively. From Shahabuddin to Ratan Majumder to G S Kabir, the art stars of their respective periods of emergence, respectively in the 1970s, early 1980s and late 1980s, all had the luck to receive recognition from within the organizational apparatus of the Shilpakala Academy's major art events including the National Art Exhibition and the Asian Art Biennale. Since the late 1990s, things have progressed, but the informal mechanism to recognize the 'best' has suffered and no initiative has been taken to assuage the limits of the current practice of “salon type' assemblage of artworks, as has been expressed by Marek Bartelik, AICA (International Art Critics Association) president, who visited Bangladesh between 16th December and 9th January and delivered three lectures on Asian Biennales and his experience in art writing.

New art always appears in the spirit of transgression; it also often attempts to overshadow/overturn the art that preceded it. And to recognize it doesn't necessarily mean a wholesale acceptance of, or submission to, the genre or mediums it uses to make its appearance. However, in the changing circumstances of global politics and the context of a society in transition, artistic language has to become embroiled in many a technologized, politicized, and even socialized form. It is fair to deduce that not all forms would have a lasting impact on art and society at large, but that they have emerged out of the current historical development, in itself a phenomenon that calls for a level-headed attempt at reconnaissance.