reading room

‘Reading Bangkok' The deflected gaze in the e/il lusive city

This is unquestionably one of the great cities of the world. – Ross King

It is tempting to read the porous polis that is Bangkok as a landscape shaped by intrusions; certainly some reviewers of Ross King's 'Reading Bangkok' (2011, NUS) have submitted to as little. Yet, King's Bangkok, an elusive and illusive city, for all its overtures to the 'other,' lends itself to anything but facile penetration. To the neo-colonizing Western gaze, there is something impenetrable about Bangkok, an 'extraordinary otherness.' King situates himself between the deflection of this gaze and the gaze itself, tracing the social production of the landscape of one of the great cities of the world, rich in its contradictions, through the layers – visual, symbolic, functional – of its built fabric. Shaped by the legitimizing acts of its successive rulers, the city that Thais call 'Krung Thep' is read as a space of surfaces, screens and masks that may well mutate (one into the other), but never to disturb what King calls the performative unification of the triad (Nation-King-Religion), the 'soothing, motivating screen' across the 'muddle' that is Bangkok and the violence of its production.

It is well-established in scholarship on Thailand that the triad, which became the modern official state ideology of the kingdom, was instrumentalized as a screen to counter the shock of Western liberalism; King's scope, though, is broader and more specific. Mobilizing theories from cultural studies to political economy, the city that emerges from vigorous probing – for there is a rather didactic emphasis on the 'unmasking'- is a landscape of juxtapositions and superimpositions. Conjuring and deconstructing apparent 'Bangkoks' through successive levels of colonization of the city, he takes us into the labyrinthine sois, circumvential ring roads and Royal Boulevards of a performative 'modernity' that co-exists beside the seemingly postmodern landscape of urban survivals amid capitalist ruins built over the filled-in klongs and rice paddies of a more boundless ruralscape. This empirically rich and somewhat circuitous book of five chapters with topographical views of the city as it was transformed, each describing a level of colonization through interlinked stories, is structured between two 'vantage points': a prologue that sets the critical juncture (2010, following the May red-shirt protests and bloody crackdown) and an epilogue that re-reads possible meanings of a Thai episteme or world-view through the reorientation of the gaze.

Emphasizing the role of foundational myths and violent beginnings, King describes the first level of colonization as 'self-colonization,' an initially imperial and later nationalist imperative that accounts for much of the order and disorder of the present landscape. Fashioned from the waterscapes of a fishing village near the seafront town of Thonburi, Bangkok grew from a trading port along the riverbank of the Chao Praya. Its foundation as the capital following the 1767 Burmese invasion of the ancient kingdom of Ayutthaya (and their subsequent defeat) marks the 'intrusion' of the governor of Tak, Taksin – not descended from any line of Kings– into the narrative of Siamese royalty. Self-colonization (i.e. consolidation of power by the conquest of the non-Thai and vassal sultanates of the North and South) was a legitimizing imperative for Taksin and his successors, who brutally deposed him, inaugurating the still reigning Chakri dynasty. This process eventually led to the reverse colonization of this same center by the periphery (via forced and later voluntary migration). King goes into some details over the legacy of continued rifts between those that constitute the 'peripheral' and the 'central,' rifts that came to define the politics of the megapolis in 2010 – when the superblocks that constitute the city became defined by the intersections overtaken by masses of protestors—and subsequently inspired the structure and conclusions of his book.

Legitimacy at this first level of colonization involves the performative unification of religion and royalty, through the embodied myth. King details the intrigue of what is now called the Emerald Buddha, tracing its appropriation, transposition and present value as an urban collection to the myth of the 'jewel par excellence' which gave the Holy Emerald Jewel and its relic the significance of symbolic center, as it shifted between the Northeast of Thailand (Lao-Isaan), Laos and then Bangkok. Urban collections like the Emerald Buddha, which was won from the Laoisians and shifted between several Wats, removed from Thonburi to Rattanakosin in the Chapel Royal, and finally placed where it remains today, Wat Prah Kheu, legitimized the right to rule and suppressed ambiguities of origin.

Juxtaposition in the form of 'the collection of the differences of partially blended communities' is discovered in the architectural inconsistencies running north to south of the ancient city of Thonburi, where the Farang Kudijeen, the Portuguese settlers, the French missionaries, the Chinese and the Muslim settlers co-exist. Cultural fusion takes on garish and subtle variations i.e., the hybridized overlaying of traces of Portuguese and French elements in the renovated neo-classical Santa Cruz Church's tribute to Italian architects Annibale Rigotti and Mario Tamagno and the Chinese elements overlaying the Holy Rosary. The Hindu and Chinese symbolism in the Prang of Wat Arun, the royal temples adjoining the Mosques and Taksin's Wat, the Shia mosques that appear as anything but non-sequitors to the Buddhist Apsaras that line Airport Road on the way downtown, all purport to belong to the landscape of illusions, in this case, that of peaceful cohabitation. King, however, reads tensions in the differential assimilation of the various minorities here, with the Muslim South being the most obvious exception to the illusionary rule. King describes the paradox of jarring, blending juxtapositions of elite and communal space but notes superimpositions even on these juxtapositions, a communitarian walkway along the Chao Phraya, resisting the fragmentation of the river by private houses on the riverbank. Superimpositions are particularly visible in the neighborhood of royal pageantry, Rattanakosin, where monuments and statues of Kings confront each other in what may be called 'obligatory forgetting/remembering', in the words of Ernest Renan.

The reading of Bangkok space as a dialectical utopia --where the idealized motif of 'house with garden by canal' becomes more and more a residential façade, in the housing estates separated from the disappearing klong-based communitarian, flowing spaces—is offered but rejected. Such apparent contradictions do not survive King's gaze. Chaotic resilience, manifest in both the slums in the periphery and the functional layers of the informal economy question the symbolic screens of the triad, considered a part of the 'richness' of Bangkok's muddle. King notes: 'Unlike the condominium blocks, (chaotic) defiances by the poor against the order of formal settlements and the rigid order along the klong in the low-income housing subject to subsequent disordering, disorder and transgression, are a survival tactic for the poor.' It is not uncommon to be walking along the heart of cosmopolitan nodes, parks, subways and shopping malls in Thanon Phahonyothin, and be suddenly confronted with klong-based rural communities. Actual farming communities on the outskirts of the city in Nonthaburi and Buaan Man Kong Bangkhen are part of a subsiding universe, yet their resilience testifies to the rich muddle of the city, even as its urban sprawl eastwards and northwards escapes these sleepy, apparent villages.

It is in the juxtapositions of the city of the modern age, inaugurated by the shock of Western contact in 1828, that King identifies a radical break and a second level of colonization. The shift from a theatre state to a performative one parallels the apparent shift from an absolutist one to a modern one. With the (superficial) civilizing missions of Ramas IV and V, modernity is performed for the West, as Royal roads (the royal way of Ratchadamnoen) are screened behind 'modern' institutions, 'styles' and veneers; screens become masks, which, in turn, determine the surface. King reads the superimpositions of Ratchadamnoen as belonging to Pierre Nora's category of lieux de memoires (places of memory), rather than mileux de memories (living memory). One is challenged to see the city as a city of mourning or nostalgia, where one mourns history or yearns for a past that is no longer lived. Yet this 'royal way' is also a space of flows, ambiguities and transgressions.

The Democracy Monument, a carved representation of a palm-leaf manuscript box holding the Thai Constitution of 1932, is but one monumental irony. Created by widening the royal boulevard (with subsequent displacement and environmental destruction), it is a performance, not for predatory outsiders, but for Thai citizens themselves (internal colonization), for whom the failed revolution is edified as progress. Four wing-like structures of 24 metres guard a round turret of three metres representing together the date, 24th June, of the failed popular revolution. The wings further represent the four branches of the Thai armed forces on top of two golden offering bowls. The ironies are multiple: The six gates of the turret represent the six proclaimed policies of the Phibun regime: 'independence, internal peace, equality, freedom, economy and education.' Yet, the bas-reliefs designed by Italian architect Feroci depict the military guiding the people. In reality, the absolutist royal walk was only superficially 'widened' towards constitutional monarchy. The image of the Queen erected beside one of the wings of the Democracy Monument hints at the tension within the triad that haunts these lieux de memoires. Similarly, the creation of the Sanam Luang monument to obscure the '76 massacre of students reveals contradictory historical impulses.

The promotion of nationalist agendas through the language of architecture, as interests morph and screens become masks, follows a less than winding route from Rama IV to Sarit. The royal passage was transformed into a grand avenue, in an essay at amnesia with the help of architect Pum Malakul's design of Grand Avenue of office buildings in Thanon Rachadamnoen in the Art Deco style. Phibun's dictatorship similarly employed the fascist inspirations of Mussolini through the Fine Arts Department's Italian architect, Corado Feroci.

King delves into cultural studies, but none too deeply, to elicit distinctions between the private and public realm of signs in Thai culture, as well as a folk idiom where paradox reigns between a formal and a Buddhist lexicon. Here a distinction could have been made between the Greek 'polis' with its notion of the family as the cornerstone of the larger unit that constitutes the city and the paternalistic and patrimonial ideologies that guided political structure from Phibun's phuman philosophy and Sarit's reactionary modernization to a corporate culture structured on the 'ties of the family.'

King's most interesting chapters conjure the transformed, 'hyper-modern' Bangkok, and it is as though one can see the liquid scaffolding of the city of 'many actual worlds'. The co-mingling of Western mimicry and indigenous pastiche results in a hybrid kitsch that, according to King, teeters on the absurd. The return of Western-educated architects in the nineteen sixties coincided with the transformation of an indigenous libidinal economy into the garish Vietnam-war-catalyzed consumption landscapes of Sukhumvit. The third level of colonization, consumption, is the most familiar: neon and spectacle, the Western mimicry and kitsch of Poseidon in Soi Nana and Soi Cowboy and the Las Vegasing of Ratchapisadek and the reverse-Thaification of the strips, as well as the pure consumption 'formal economy' of Silom. While modernity may be associated with the high internationalist style of the numerous neo-classical facades of the Royal buildings (i.e. Ananta Samakorn Throne Hall) and hotels, it is in the 80s that what may be called a Thai postmodern is ventured: Rangsan Toruwan's Egyptian-Roman hybrid of The Gran Hyart Erawan Hotel, the neo-classical domes and Gothic referencing of Krisada Arungwonse, Aphai Phadermchit and Ong-art Staraphan.

COURTESY OF SUMET JUMSAI

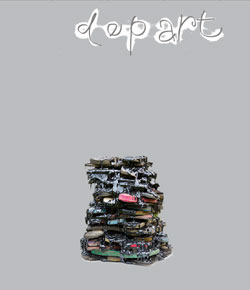

The landscape of ruins, the fourth layer of colonization, testifies to the violence of the social production of the latter. King elicits the most haunting example of the social construction of Bangkok's ruins in the unfinished BERT pillars, post the Asian crash of 1997 and the ghost-like Sathorn Unique, a trace of the dream of Rangswun Taruswn' 'Silom Tower' (the smaller brother of the State Tower, imagined as a 47- story Neo-classical behemoth). King goes into some detail on the remnants of failed projects, i.e. the fixed rail public transport abandoned for the automobile inflicting a change in the nodes and arteries of the city, and the construction of a haunted landscape of ruins, with the attempts to salvage the abandoned plans by developers in 2007 and 2008.

In the landscapes of the mind, the final level of colonization, King analyzes Thai educational institutions and cultural formations in their relation to the colonization and liberation of the mind and to the marriage of institutions to the state. His critique of the wholesale application of Western modernism and postmodernism in such institutions as Silapakorn University where the application of Italian images of nationalism to Thai epistemology is sharply different from neighboring countries like Malaysia, where a vernacular language in architectural and general education has been allowed to flourish, is scathing. This is tempered, however, in an acknowledgement of the vernacular architecture, promoted by Rama V's espousing of a Royal Preferred Style for commoners' housing. He gently praises Rama VI's Thai beach-front-Palace in the style of the Thai stilted houses, shaded and open to the breeze as a reworking of the potency of tradition through the application of traditional motifs to a much larger scale.

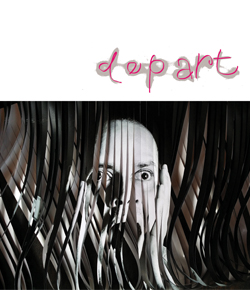

Yet King is harsh in his critique of the superficiality and 'eclecticism'—a preponderance of style over reflection—that is synonymous with the effects of such hybridity. He notes the exceptions of the unique personalized creations of Sumet Jumsai and the neo-traditional salas of Montien Bounma. Jomtien's individualist expression of Cubism with his signature commentary on modernity itself, The Nation newspaper's towering abode, is a ludic expression of an 'Editor at his desk.' Jomtien regards Cubism as an expression of the different stages of thought, as in Le Corbusier's Cubist paintings. The Nation tower, he explains, shows process, the editor in his circuitries, and is an expression of architecture as painting: 'It is an expression of a painting that shall be built, starting as three vertical planes which then continue to become partly curvilinear, then flows into a free play of curves.' Other examples of Sumet's experimentation include the Hilton and Athenee hotels, where the use of light and technology is elegaically harmonious, and the iconic Robot building.

The salas of Montien Bounma, artistic meditations on the Thai experience of ephemerality and Buddhist immateriality, are seen as exceptions, as well, to the notion of a non-reflexive mental landscape producing absurd kitsch, hyper-modern assimilations and ruins.

The sala, a traditional open pavilion comprising four posts and a roof, can be seen everywhere in Thai architecture, from restaurants, waiting abodes, resting places, parts of much grander edifices (i.e. The Royal Palace) to riverside mosques, glinting gold beside a glass building. But King describes Bounma's art as deconstructions of the elitist appropriations of such traditional motifs, where his meditations on the 'Sala of the mind' become a signification for transformations in Thai-Khmer spiritual architecture, a source that can then inspire further transformations in 'modern' space. With this final chapter and the epilogue that follows it, our gaze on 'Bangkok' is reoriented.

Here is where King's critique of the non-reflexivity that appears to be characteristic of Bangkok space shifts to a recognition of indigenous spaces such as the historical dialogue embodied in the spatial 'discourse' of Thammasat University's Memorial Sculpture Garden, as spaces of resistance to the superimpositions of 'lieux de memoires' (places/monuments of memory, a la Pierre Nora) over 'mileux de memoires' (living memory), so pervasive in the cityscape. The unrevelling, that happens there, is best left to the reader's own journey.