navigator

Layered monologue and the game of throne

Time, Coincidence and History, in the main, is a space for crystallizing the vestiges of colonial and postcolonial history covering in its broad sweep the legacies of social-political conflicts, religious parochialism that places identity over piety, and, finally, the body as a carrier of the pathologies of time. This intermedia art exhibition places in an imposing aesthetic order references to all of the above and more in an orchestrated display of sculptures (including kinetic pieces), moving images, drawings, and dried twigs and brunches presented in a bountiful display and leaves and sprouts preserved inside small transparent resin blocks.

In many a large sculpted object artist Dhali Al Mamoon mediates the body as material, or material as indication of the body whose structure in its recognizable contour has been willfully made to disappear. If Francis Bacon 'dismantled the face', to use Gilles Deleuze's phrase,* Mamoon disavows the corporeal body or the structure in order to appropriate the vertebra and tresses of hair as his central tropes – resizing and restructuring the former and incorporating the latter as an antidotal object mining their soft, melancholic constructions. To forward a conglomerate of references to the civilizational malaise, which Mamoon addresses with an apparent emphasis on the anthropocene, one witnesses the observable, haptic as well as audible traces taking the stage to be re-formed into the final choreography. These are collectively invested into the creation of the perceptual substratum that is set forth as a monologue of an artist trying to leave an affect.

The narrative remains subsumed in two structurally different freights since Mamoon forms his language around finished sculpted forms and in an exclusive reorganization of natural materials. With each piece of sculpture assuming an existence independent of the other and the dried branches and twigs amassed to challenge the given space, this exhibition attempts to deprotienize the art scene that has too often witnessed the aesthetic being equated with the retina-pleasing dimension of the work which by any standard can easily be deemed superfluous. There is this other side to such an aesthetic gambit: the withdrawal from the retina for some affords an opportunity to send a 'loud message' in opposition to an 'undercurrent' released for unconscious internalization of the viewer. In Time, Coincidence and History the perceived undercurrent flows in different directions touching on sensations that can be described as 'terrestrial', which, in some pieces, is pushed to its limits, so much so that it borders on the 'celestial', to employ Deleuze's typology of sensations.

Mamoon holds out a thread of connected as well as disjointed narratives in this exhibition forming a language which is not expository of the events or mishaps, but a response in the form of condolence/commiseration. Not that the artist devises esoteric codes through which he passes all the sentiments and sensations. To decry natural degradation and human folly he puts out in the open some morphed and demorphed objects in the hope of transcending their objecthood. The 'spatializing material structure' or the bones or enlarged leaves thus collapse into object of meditation – they become lexical entries adducing to an open-ended narrative.

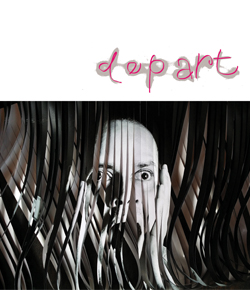

The Viceroy's throne – an important metonym for colony – is referred to in the work Lat Shaheber Chair (chair of the viceroy) which, following Mamoon's intervention, appears as a symbol representing two subsequent eras – one that of the last Mughal emperor Shah Alam II and the other that of the usurper of power – the British colonial rule. In fact the work surrounded by two other components is a reminder of the Treaty of Allahabad, signed on 16 August 1765, between the Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II, and Lord Robert Clive, of the East India Company, which enabled the latter to launch a regime of commerce which soon proved to be a pretext for a final colonial takeover.

A perfect vertical cut divides the chair in two pieces that are set on a pedestal couple of feet apart. The left portion replicates the original from a photograph and is black and the right part takes bone-like structures as its building blocks which are painted white. This re-inscribed colonial relic placed at the entrance of the gallery sets the tone for what one would encounter inside.

Once inside, in the front room of the gallery, the space stands transformed with myriad twigs dangling from the ceiling greeting the onlooker into a considerably eerie environment. The two video works on two facing walls recall nature. One follows a snail or two in a mildly phantasmagorical film which draws its strength from both the reality it represents and its inversion into a negative footage on a loop.

What Mamoon declares in a conversation with poet Sajjad Sharif, artist Naeem Moheimen, et al, is of crucial import as to the context of his deauthorialized forms and shapes. No wonder that he places 'language' over mimetic learning which enables him to shun the form-content duality: 'I tend to prioritize language over trend. When I work on the subject of genocide, my aim is to concretize that phenomenon.' The two aspects, the language and the communicable physical objects that stand for the real event, lend his works a silent drama. One can easily expand on this theme in light of what poet Sajjad Sharif refers to as 'the pull between the drama enacted and the stillness exuded,' discernable in Mamoon's current oeuvre which remains lodged between grandeur and lightness with an obvious tilt towards the former. But the mind frame behind this also must be brought into light: Mamoon, in giving shapes to what is inexpressible resort to mute expressivity of things made and agglomerated/collected and displayed in a certain unorthodox manner. Since the inexplicable arises out of the most traumatic of events in history, like Maria Pia Lara, the Mexican public intellectual, Mamoon too unresignedly rests his faith in the fact that, ‘the most inhuman site of humanity allows us to say something’ and ‘that someone is “the witness”.’

Yet, what is exposed is embedded in what has been 'saved as remnant'. The sheer physicality of his pieces is an experience in itself. By conceiving this linguistically effusive forms as 'presence' coupled with the intention of producing them as relics – as a testimony of the past as well as the ongoing catastrophe of natural and social degradation in the modern age, Mamoon bears the burden of the witness, or rather let the objects be the witness by proxy. Thus new forms and shapes continue to emerge in consonant with his motive. They answer to the same consignment of sensation stated above – often touching on the edges of 'celestial sensation' though they are primarily made to remain decisively lodged in the vicinity of 'terrestrial sensation.'

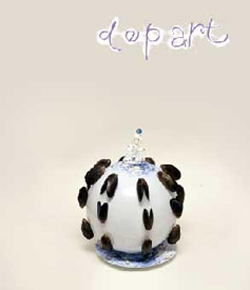

Toward Purity and Sacrifice Beauty are new forms made to adhere to a linear ordering to echo human condition and the stasis pertaining to logocentrism. Both pieces make strange the sight and sound associated with the actual elements with obvious allusions to the functions they once had served in real-life context. The former with its ossified water from a tap and the latter by intentionally confusing the floral motif with old gramophone horn expand on the artist's earlier engagement with troughs, water and metal taps which he used repetitively in one of his elaborate installation in 2004, entitled Water is Innocent.

Interestingly, repetitiveness for Mamoon is often translates into regression towards the elemental – a way to shave the details or performative elements off to render his structures static and grand. Here lies the correspondence with epic and the architectonic arrived at through the codes of tragedy. However, 'like icebergs', to use artist's own formulation, they are immersed in a stratum of knowledge and understanding – those that were absorbed by the artist through his appearance on the art scene first with an obvious political voice as a member of Shomoi, or Time, than as a shape-shifter tackling the anthropocene – set to trace the human footprints on nature responsible for its slow and gradual defacement.

In the same site the entry of two works on faith and the make-belief edifices it often get confused with seemed to have inaugurated a new approach to exhibition-making. On a wall inside the gallery that should otherwise occlude our view, the artist inscribes a view of a mehrab-like form – elegant and anxious at the same time. With areas of chipped plaster the work makes the red bricks visible – perhaps to allude to the gradual ruination of faith by daily routine of pretenses besides the wholesale secularization of the religious rituals.

In contrast to the above piece which one might feel does not fully annex us to the world of piety, one that seems to take the shape of a protrusion from the wall, initiating a coup d'état in this gallery space – unfolds as an enhanced encounter with the mehrab as is seen from outside of the mosque in reality. With its steel sieve-like perforated surface it invites a peek without allowing one to understand the source of light it hides inside. A cumbersome construction, it is an indeterminable form – its dissociation from the narrative of negation and criticality makes it appear more like an enigma.

Between the material culture and the immaterial truth about human existence there lies the grey areas of human follies – and this is the locus from where Mamoon operates, working in opposition to the dictates of the mainstream, not as an objector or purveyor of truth but as a surveyor trying to come to grips with the symptoms to arrive at his own prognosis. In this he extends the project of Bacon, et al, in a subterranean manner, into the violent epochs of the new millennium. Bacon's 'heads', faceless and lost as they seem, were once retooled by this Chittagong-based artist and art teacher as tendentious narrative against the political crises brought forth by the subsequent military governments, at present the remains of the body as well as nature and the body-politic seem to have come together to affectively harp on the continued erosion palpable in the knowledge centers, communication networks and most of all in the obvious displacement of the human subject trying to assume a position against the tide of our time.

‘Time, Coincidence and History’, a solo exhibition by Dhali Al Mamoon, ran its course between 23 January and 19 March 2016, at Bengal Gallery of Fine Arts, Dhaka.

* Gilles Deleuze, Body, Meat and Spirit, Becoming Animal, Francis Bacon, Continuum, London/New York 2005, p 15.