depart file

11 theses on representation plus a few more reflections

1

Art overburdened with the task of recording the real, or committed to presenting it as realistically as possible to be considered as true reflection of the received sense-data is often referred to as realistic – a category that actually stands proxy of 'naturalism'.

2

The Ruskinian diktat is apparently about a sincere invitation to rigorous study of nature. The question is: does it lead to the devaluing of the aesthetico-political content in art by lending primacy to what we assume to be as its material aspect? John Ruskin(1819-1900), through his insistence on verisimilitude, saw art as the mirror of nature, which for him was naturalism achieved through painstaking application of skills.

3

Skill over expression also equals primacy of the ocular over all other senses including the haptic one, which may even force one to dismiss the universally lovable atmospheric works of Turner, as was the case when Ruskin looked at them with the expectations of a 'naturalist'.

4

Is naturalism about objectifying nature? Subjecting nature to dissection, inspection and study may be the prerogative of the scientist, but treating nature as an object of contemplation in the name of art only serves to ascertain the divide between humans and their natural surroundings, and also between experience and knowledge, body and mind, esoteric and exoteric, etc.

5

Rousseau argues that writing may corrupt the original nature of language. Accordingly, representation of reality in the vein of skillful delineation (which actually is, interpretation in the naturalist vein, or a cog the wheel of the symbolic order – through which, historically works of art are produced like any other semiotic system) may dilute our other sense faculties, or at least play a domineering/oppressive role over them. Thus, life becomes a play-field for observable truths leading to the final equation: only what is observable is true, the basis of Western rationalism of the enlightenment era.

6

Not everything is observable, though modern life is geared towards its antithesis. 'Derrida, famously, challenges what he calls the “metaphysics of presence”. What he is challenging is not the reality of presence as such, but the notion that we can arrive at some pure presence of a thing, a moment, a self that is unmixed with anything other than itself. A pure instant of time that is not filled with past and future; a pure ego that is not a product of training, a pure substance uncontaminated by accidents.'

7

But isn't the 19th century English naturalist gaze seeks to define a painting as the exact representation of what they see in the light of the day – clearly, objectively and stubbornly so, to ensure that what is real has been captured or at least dealt with fully and conclusively? Is it founded on the strong, and also misplaced belief that there can be an observable, objective and absolute reality out there for the artist to duplicate?

8

Art as the mirror of the world is a figment of imagination that seeks to validate its imagined yet linear trajectory by assigning it the value of the 'actual', thereby enforcing an interpretation of representation as if it was the exact replica of the real.

9

Reality, set against the unreal, has always been accepted as 'constant' – a source which enables the artist to be authentic against the flow of constructed truths; it is a notion that confuses the fact that all representations are in the most part human construction.

10

Before one is engaged with reality one needs to be aware that it can never be rescued from the subjective/interpretative web which always alludes to the fact that reality is an integral part of the mind-body conjuncture. And most of all, reality when considered only as an observable phenomenon in its contour and texture is actually a fraction of the 'whole'.

11

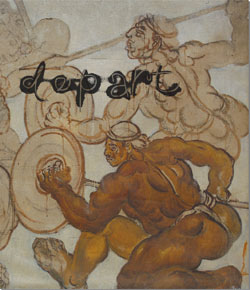

Existence of trompe l'oeil, favoured by Europeans in the classical era and even long after that, is proof of realistic representation serving as a device to establish the make-believe world within the worlds in which we reside. It is also proof of the obsession of the Western classical civilizations with visual tactics that enable the artist to create an illusion – though in fragments and pieces – of the observable world.

In anticipation of a life that imitates art

Notions and norms rule over our regular evaluatory processes, or even impede the intuitive faculty through which we may sometimes become 'enlightened'. Thus any interpretation of art – in the abesence of logic or revelation – springs out of the every-day confusion by which the modern-day knowledge-base is afflicted.

One form of life can be an imitation of another – as is demonstrated by people who orientate their life inspired by the represented world – the media, or a superior 'model', to which they aspire.

Fashion victims are the imitator of attires and accoutrements, whereas the victims of lifestyle are the imitator of aesthetic choices of others, as ethos is often intangible and as such remains elusive. Perhaps it is part of modern existence that we, by way of mimicry, appropriate what lends us a sense of importance, which of course is about conforming to a given lifestyle and discipline or regime perceived on the basis of visual-data.

And what makes us 'mimic persons' per se, even if it doesn't show in our sartorial leanings, is when, through the refashioning of the 'self' by imitating the passion and prejudices that the consensus reality or the 'world order' spawns, we almost become one with our perceived model of a modern/contemporary person.

The word 'almost' stands proof of the fact that personality too cannot be fully imitated, as such life imitating life throws life in a catch 22 situation. So, we rest the case for imitation here and now.

Art copying nature? Or art drawing on trends and techniques of representation only?

Art, on the other hand, can be a copy – an offshoot of certain other art forms, but never an initiation of life, at least not in the form the 19th century European naturalists would have us believe.

'Multiple attempts at drawing the same tree by an artist may lead to varied results,' as has been declared by Monirul Islam, the expatriate artist living in Spain for the last 40 or so years, is a commentary which points to the fact that a real tree cannot be captured in its entirety through representation.

Monir's rebuttal to a question raised by a young artist only brings to light the fact that an artist possessing the required technical finesse will always fail in his attempt to produce a 'replica'. This inability throws us at the centre of an age-old mis-perception that nature in its 'actual visual presence' can be enshrined within the space of an artwork that apparently is produced by an artist who is a keen observer. A rationalist in the vein of the European

Enlightenment philosophers, even Rabindranath Tagore, when tried his hands on art, attempted to harness the energy of the visible world, eschewing verisimilitude.

As for producing a 'copy of the copy', the celebrated phrase coined by Plato, who saw the changing physical world as a 'poor, decaying copy of a perfect, rational, eternal, and changeless original,' a lot of mis-perception gathered around it.

Augusto Boal, advocate of 'simultaneous dramaturgy', throws an adequate light on the issue while attempting to disentangle the very idea of art being a copy of nature. He rights some wrongs by letting us in on his interpretation of the age-old misrepresentation of a text by Aristototle on 'mimesis'. Furnished below is an extract from Boal's seminal book that traces the idea of mimesis of a major player in Greek philosophy:

The first difficulty that we face in order to understand correctly the workings of tragedy according to Aristotle stems from the very definition which that philosopher gives of art. What is art, any art? For him, it is an imitation of nature. For us, the word "imitate" means to make a more or less perfect copy of an original model. Art would, then, be a copy of nature. And 'nature' means the whole of created things. Art would, therefore, be a copy of created things.

But this has nothing to do with Aristotle. For him, to imitate (mimesis) has nothing to do with copying an exterior model. "Mimesis" means rather a "re-creation". And nature is not the whole of created things but rather the creative principle itself. Thus when Aristotle says that art imitates nature, we must understand that this statement, which can be found in any modern version of the Poetics, is due to a bad translation, which in turn stems from an isolated interpretation of that text. "Art imitates nature" actually means: "Art re-creates the creative principle of created things."

Art equals maya, or a semiotic system?

An excerpt from Rabindranath Tagore's 'Religion of an Artist'.

'…Thus we have come to realize in our own person the two aspects of [ artistic] activities, one of which is the aspect of law represented in the medium, and the other the aspect of will residing in the personality.

Limitation of the unlimited is personality: God is personal where he creates.

He accepts the limits of His own law and the play goes on, which is this world whose reality is in its relation to the Person. Things are distinct not in their essence but in their appearance; in other words, in their relation to one to whom they appear. This is art, the truth of which is not substance or logic, but in expression. Abstract truth may belong to science and metaphysics, but the world of reality belongs to Art.

The world as an art is the play of the Supreme Person revelling in image-making. Try to find out the ingredients of the image – they elude you, they never reveal to you the eternal secret of appearance. In your effort to capture life as expressed in living tissue, you will find carbon, nitrogen and many other things utterly unlike life, but never life itself. The appearance does not offer any commentary of itself through its material. You may call it maya and pretend to disbelieve it, but the great artist, the mayavin, is not hurt. For art is maya, it has no other explanation but that it seems to be what it is. It never tries to conceal its evasiveness, it mocks even its own definition and plays the game of hide-and-seek through its constant flight in changes.'